Illustration © Kaitlynn Copithorne

When my mother was a little girl, children in Vera de Moncayo who misbehaved were warned about the witches of Trasmoz. They might come scoop you up and take you away on their broomsticks. They might cook you in a great stove. They might eat you.

Once, my mother had a terrifying dream. As she lay in her bed, a woman dressed all in black flew into her bedroom, in through one window and out the other. She was Tía Casca, the greatest and most feared witch of Trasmoz, and she was there to get my mother. My mother followed after her, flying out the window, not even holding onto a broomstick, just body and air.

Vera de Moncayo, the village where my grandparents were born and died, and where my mother grew up, is located in the province of Zaragoza, Spain, sitting upon the slopes of the Moncayo range. Here, villages are scattered like rocks, their skylines of tiled roof and church spire as rugged as the Moncayo itself. They sprawl along the mountainside, connected by straight roads and serpentine trails, which crisscross the arid land’s deep ochres, reds and greys of sandstone, clay and slate.

Vera de Moncayo was the scene of many of my own childhood summers, left in the care of my grandmother, and the never-ending stream of chordones, wild raspberries that spread in brambles across the comarca, or county, and which I would pick with my grandparents and throw into a bowl, sugar sprinkled on top.

From Vera, walking south towards the imposing Moncayo, the straight road leads to Veruela Abbey, historical seat of the Church: the monastery where the great poet Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer, possessed by the mountain and by the legends of the comarca, wrote his Cartas desde mi celda.

Trailing northwest from the monastery (or down the west road from Vera), a castle tops a small hill. Its ruined outline stands guard from the distance, a cluster of houses spread out under its watch. Here lies the village of Trasmoz, land of the witches: the source of so much inspiration for Bécquer and of so many nightmares for my mother.

Vera, Veruela, Trasmoz. These were the constants in my mother’s life in the ‘60s: three points of a triangle, meeting at crossroads. And overlooking them all stood the Moncayo mountain, casting a net of enchantment across the comarca, its spell reaching into the corners of dim stone houses and stinking cattle sheds.

Capped by a snowy crown, the Moncayo thrusts upwards into the sky, sometimes emerging from a cloud of mist to give the impression that its summit is floating in mid-air. It is the site of many stories and legends and a witness to the many events that, throughout history, have haunted the lands of the comarca.

If I close my eyes, I can conjure it in my mind, a watchtower behind a curtain.

*

During the many summers I spent with my grandparents in Vera, I had no sense of time. In the mornings, I would wake up and turn the TV on, uncertain if I would catch the next episode of Xena: Warrior Princess or if it had already aired. Even as a child, I was already fascinated by the familiar figures of the Greek pantheon, and by the sense of a great mythical otherworld out there just beyond my grasp. Xena was my heroine because she could wield a sword and confront this world head on. What was more, Xena’s sword protected her from a world of men, yet one where she was an active warrior and not a victim. Her armour was strong, but it was also feminine. Her power hadn’t been granted to her, it emerged from her own daring and skill.

On these mornings, my grandmother would flutter around me to ensure I ate my breakfast. My grandfather was invariably angry, shouting for things with a violence that made me recoil, and my grandmother did his bidding, fetching him what he wanted, preparing his meals, cleaning after him. But I always felt that there was a fortitude within her that he couldn’t touch. A way that she carried herself, remote and collected, as if she held some kind of secret, like a spell.

Next to the kitchen there was a small sitting room, where my mother’s old copy of Little Women lived. This book seemed to me like a doorway into my mother’s childhood, but I was too young to read it. I only stared at its cover as if trying to fathom some mystery. My mother’s old toys were in this room too, stashed away in the cupboards: small suitcases filled with toy tableware, with which I served guests at my imaginary restaurant. Seeing these possessions of my mother’s held an uncanny fascination for me; it was as if the ghost of my mother-as-child lived in this room too.

I can distinctly recall the smell of the room, which filled it like a cloud of must and cotton candy. It came from the cupboard where my grandmother kept her baked goods, and has come to dominate all of my memories of Vera. It was from the rosquillas, doughnuts of sorts, but tougher like pastry, and as snow-capped with sugar as the Moncayo. My mother still buys these pastries sometimes, on her occasional visits to her parents’ graves at the village cemetery, and their smell comes to fill my parents’ kitchen too.

Of all my memories of those summers, what I most remember is my grandmother. She filled the house like the sun. She seemed to hold the fabric of my world as tightly as she could. She was the rare kind of person who offered unconditional love, no matter what.

One evening, when I thought that my parents—away at some conference in Chile or Mexico—were due to return and take me home, I walked into the coolness of my grandparents’ house through the string door curtain and climbed the stairs. My grandmother met me at the top.

“They’re not here,” she said. “They arrived home too late and are tired, so they will drive up tomorrow instead.”

My heart fell to my feet, my aching for my parents so bone-deep it was almost unbearable, but I tried to erase it from my face. But I wasn’t fooling Grandma. She had a cunning eye that could see right through you.

“La paciencia es la madre de la ciencia,” she said, and smiled. She was full of sayings, my grandmother was. “Pan con pan comida de tontos” (bread with bread, meal of fools), she would reprimand my grandfather at mealtimes when he reached out for the bread basket one time too many. Or “más sabe el diablo por viejo que por diablo” (better the devil knows for being old than for being the devil). Or my favourite of all, when I burped: “está mal pero descansa el animal” (it’s wrong, but it soothes the animal).

Disappointment wearing me down, I went to the bathroom and cried. Later, my grandmother came into my bedroom. She had decided she would sleep in the same room as me. She started to change and I remember feeling embarrassed about her nudity. Her body, already old and hunched, saggy and stretch-marked, seemed so foreign to my own. I could not imagine I would ever have such a body. But she didn’t feel ashamed like I did; she felt at ease in that bedroom with me, enough to shed all her clothes.

To fill up those long summer days, I remember walking up the main road southwards in the direction of the monastery to a children’s playground. Later, my mother told me about similar walks she and my grandmother used to go on, but they would have walked farther, all the way to Veruela Abbey where, years later, she would marry my father.

There is a wedding picture of my mother in my parents’ living room, taken at Veruela. She is dressed in white but forgoing a veil. Small white flowers adorn her hair.

*

I first visited Veruela Abbey as a child. The abbey, dating from 1146, has an air of the gothic, with its crenellated walls framed by turrets and its cavernous cloisters which give the impression of a whale’s backbone. Bestiaries adorn the columns of the church entrance and the cloisters: eagles, monsters and dragons standing guard against undesirable enemies.

It was only recently that I learnt about the most notorious enemy of the abbey: the village of Trasmoz. In fact, the two have a long and incredible history of feuds. I discovered this almost by accident, years after moving to the UK. I was visiting my parents in Spain and, during our evening TV ritual, my mum changed the channel to a TV programme about Trasmoz and its connections to witchcraft.

“Look, that’s Trasmoz,” she said. “The village next to Vera.”

I watched with growing astonishment as the story of Tía Casca, a woman accused of witchcraft and pushed off a cliff by the inhabitants of this village, was enacted on-screen.

“Wait a minute,” I said. “There were witches near Vera?”

“Yeah, that was the legend,” my mother replied.

I stared at the programme wide-eyed, barely able to contain my amazement; so many summers spent in Vera and I had never heard about Tía Casca. Had this woman really existed? Did she actually practice witchcraft? And what had happened to her? The narrative laid out by the programme was compelling but, by then, I had already learnt to mistrust the stories passed down to us, particularly when they revolved around witches. More than anything, I wanted to visit Trasmoz and see for myself, but when I suggested this to my mother she only offered silence in return, so I didn’t dare ask any more questions. My mother didn’t like to talk about her childhood. So I stashed this knowledge for later and, instead, sank into a frenzy of research.

In the 13th century, Trasmoz was a powerful fiefdom, independent from the authority of the Catholic Church. The Church wanted to force Trasmoz to pay taxes to the monastery, and began to spread rumours that witchcraft was being practiced within the walls of the hilltop castle. As a result, the abbot of Veruela convinced the archbishop of Tarazona, the largest nearby town, to excommunicate the entire village. The rumours of witchcraft stuck and the castle of Trasmoz came to be seen as a place of terror: the locale of the witches’ sabbath. These witches were said to fly to the castle upon their broomsticks, where they practised perverse rituals. And of course, there is nothing like the suggestion of womanly sin to sow the seeds of legend.

But that didn’t mark the end of the story. In the 16th century, a feudal war broke between Trasmoz and Veruela over the use of water from the Moncayo Range, which passed by the monastery before arriving in Trasmoz, and was an essential resource for the village amid the arid landscape. The abbot had decided to divert the course of the river and the lord of Trasmoz, Don Pedro Manuel Ximénez de Urrea, appealed to the King, Ferdinand II of Aragon, who ultimately sided with Trasmoz. Stripped of its legal authority, the monastery turned to its spiritual authority, and with the explicit permission of the Pope, Julius II, the abbot launched a curse against the village, tolling the church bells in the early hours of the morning so that the entire village would hear it, while reciting the words of Psalm 108:

Give us aid against the enemy,

for human help is worthless.

With God we will gain the victory,

and he will trample down our enemies.

To this day, Trasmoz remains the only village in Spain to be both excommunicated and cursed, and its reputation as a site for witches’ sabbaths lives on.

*

When I was twenty-five, my parents and I took a trip to South-West England, where I wanted to research West Country witchcraft for a novel I was beginning to work on. I was fascinated by how witchcraft there had been informed by the land, and had been reading about the workings that cunning women used to carry out in those regions: powders, liquids and charm bags using herbs and plants foraged from nature.

One morning, as we sat in the breakfast room of our B&B, my mother told me the worst story of her childhood.

“Did you know that, when I was little, I watched your grandma almost die?” she said. I dropped my toast and she told me, purging it out from someplace within her that I hadn’t known existed.

When my mother was a little girl, she was the thing my grandmother loved the most: they were as if stitched together. It was always just the two of them, my mother and my grandmother, two afterthoughts in a house that was dominated by the spectre of the previous wife (died in childbirth), the leftover children (bitter and cruel) and the residue of the war (a direct affront to the virility of my grandfather, shot in the thigh).

By the time my grandparents got married, my grandmother was almost forty and considered past child-rearing age—her fiancé had died in a car accident during the war and the list of eligible bachelors in Vera had since dwindled. My mother was born soon after, and her older siblings never forgave her or my grandmother.

To escape the hostility that permeated their home, every morning my mother and grandmother set out on their daily walks, tracing the veins of the comarca as if their lives depended on it. Sometimes they would walk the long straight road towards the monastery, sometimes the winding road towards Trasmoz. As they left the familiar ground of the larger Vera and began climbing the hill towards Trasmoz, it was as if the two were entering a fantasy dimension, with its ruined castle atop the hill and the rickety village underneath. Here was the land of make-believe, a place where anything seemed possible. My grandmother would tell my mother about the witches of Trasmoz, and all along the way they picked wild herbs: rosemary, oregano and thyme.

Herbs, in my mother’s world, were a thing of magic, but also a thing of terror.

Thyme, infused in hot water, was good for colds and the flu, or so my grandmother swore. The thistle of the comarca adorned every Christmas Eve plate, and to this day still does in my parents’ home, peeled, soaked and slow-cooked in an almond sauce.

But other herbs cast a shadow over my mother’s childhood. The kind you collect in secret, grind and steep and hope that the neighbours won’t see. Spain is a Catholic country, and it was especially so during the decades-long dictatorship that my grandfather almost lost his manhood fighting for, and which my mother was born into. But my grandfather didn’t want another mouth to feed, and his word was the law.

There is a violence to men who give and take away. When my grandmother fell pregnant once again—against all nature—he forced these herbs into her gut and didn’t care that they almost killed her. It was my mother, still a child, who watched over her for days, tending after her, administering salves and holding her hand as she slipped in and out of consciousness and almost died. She was the only amulet between her mother and the violence in that house.

Now I wonder if that was the first time it happened. Perhaps my mother’s existence is a miracle of flesh and cellular stubbornness. Perhaps she was an unwanted child too, but I know my grandmother wanted her more than anything in the world.

*

The history of witchcraft has come to us filtered through a categorically male gaze. We know the stories of witches—or of women accused of witchcraft—because we have heard them from the men who accused them.

It was no different with Trasmoz, and perhaps this is the reason why the story of a woman horribly murdered has come to be veiled in legends of devilry and wickedness. One has to dig deeper to find the forgotten story.

Here is the story that is remembered. It is the story I learnt from that TV programme and the one that has stubbornly stood the test of time, obliterating all else.

The year was 1864 and Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer, the Spanish Romanticist poet, retreated to Veruela Abbey to immerse himself in the landscape of the Moncayo while recovering from tuberculosis. Here he came across Trasmoz, stumbling suddenly upon the view of the ruined castle perched on top of the hill. The scene compelled him to walk towards the village, up one of the trails that connects Veruela and Trasmoz.

It was on this trail that he first heard about the witches of Trasmoz, whom he wrote about in his epistolary work Cartas desde mi celda. Bécquer recounts becoming lost and disoriented while on the trail and seeking directions to Trasmoz from a shepherd. The shepherd, turning taciturn, warns him not to take “the route of Tía Casca” and tells him the story of this infamous woman who, only four years earlier, had been accused of witchcraft by the inhabitants of the village and pushed off a cliff. According to the shepherd, the spirit of Tía Casca, “forsaken by both God and the Devil”, still haunts this trail, and sometimes, mimicking children’s cries, will draw in naive walkers and push them off the precipice. Casca, as he describes her, is an old woman with “whitish tangled strands for hair that entwined around her forehead like serpents” and a “hunched body and hideous arms, angular and dark”.

The shepherd then tells him of the events that led to Casca’s death: how the witch stood accused of a number of allegations, including cursing a mule, brewing poisonous herbs, giving a child the evil eye by picking him up from his cot and spanking him at night, seducing a village girl and, finally, bewitching the entire village so that a deadly epidemic fell upon it. The shepherd himself claims to have seen with his own eyes how the men—“wretched men who did a good deed for the people of the comarca”—walked towards her carrying rocks, clubs and knives, pushing her towards the precipice while she cried bitterly, kissing their feet and asking for mercy. Finally, one of the boys delivered the deathblow and she fell into the abyss.

Of course, after hearing this story, curiosity overtakes our Romanticist poet, who later arrives in Trasmoz and finds Tía Casca’s sister. He describes her as “tall, spare, wrinkled” with “a beard of greyish hair” and a “hooked nose”. There is no sense of sympathy for this woman, no desire to hear from her own sister who Casca had really been; only a morbid awe at the possibility that she, too, might practice perverse rituals:

She was crouching close to the hearth, surrounded by a number of old odds and ends—pipkins, jars, kettles, and copper stew pans; the glare of the fire over which she leaned casting fantastic, weird reflections against the walls. She was boiling something in a pot on the fire, which she occasionally stirred with a spoon. Very likely it was a potato-stew for supper; but, deeply impressed with the scene presented to view, and with the above legend still ringing in my ears, I could not help calling to mind—on hearing the continual boiling and hissing of the stew—that diabolical mess, that horrible, nameless thing, which Shakespeare so vividly depicts of the witches in "Macbeth."

Tía Casca’s sister, he tells us, is said to manifest the same talents as Casca, as is her daughter and her own daughter in turn.

*

It is a sunny winter’s day and I am driving up the winding road when we glimpse the castle upon the hilltop. It sneaks up on us as I turn a bend on the road and—abruptly—there it is, sticking out of the hill. The castle is a thing of ruins, sitting unbudging at the top as if it’s been biding its time all these years.

I have waited until near the end of my holiday in Spain to bring up Trasmoz, in the hope that my mother will grant me this final wish before I set off again across the ocean. Knowing the right timing to ask questions is a skill I have learnt from a lifetime as her daughter. Más se gana con miel que con hiel (you get more with honey than with bitterness). To my surprise, she has agreed, and I’m wondering if she has truly softened with age.

It’s been years since I began my research into the history of witchcraft: the folk magic—salves, amulets, spells—that women devised in order to protect themselves from poverty and violence, the ancient belief in an otherworld just beyond reach and, of course, the carnage of the witch hunts. I learnt about all this with fascination but from afar, looking to places like Cornwall and Devon as hotbeds for this kind of magic. Nothing could have prepared me for the knowledge that, all this time, there were already witches in my midst, in my mother’s own land.

The day is hot for January and the sunlight floods the dry land. The landscape is so quiet that it feels like there are things being whispered in the wind.

My mother is silent, which is always a bad omen, but she has donned one of her most extravagant electric blue coats with matching tights and her manner is as defiant as that of a cat ready to pounce. “Being strong” has always been my mother’s most important quality, and one which I have more often than not fallen short of. Of course, now I know that “being strong” was just what survival meant in these lands.

Still, the village sparks her memory and she tells me about walking this trail with her mother, and about picking the herbs. I want to drink in every detail and store it away for later, but I know I can’t ask too many questions. I wonder what it must be like for her, to step back in this fantasy land that was her and her mother’s only escape from the bleak world they inhabited.

The village is deadly quiet as we walk past white facades and blue doors that give the impression of a labyrinth of sand, and streets that bear our family names.

Today, Trasmoz has fully embraced its history of witchcraft, which is delightful. Broomsticks and iron horseshoes adorn windows and balconies, cats roam the empty streets lazily, bundles of thistle hang above doorways to keep evil spirits at bay. By front doors, plaques announce the residence of the various “Witch of the Year”. Apparently, the title has been granted to female citizens of Trasmoz for over a decade.

As we reach the summit and arrive at the threshold of the old castle, the entire comarca is rolled out around us, all red and brown plains and, in the distance, almost a mirage in the squint of the sun, the snow-topped peak of the Moncayo. But I am not interested in the castle. I am looking for the monument to Tía Casca. I spy it from the hilltop and climb down towards it.

The monument is a modern wrought-iron sculpture of a woman holding a broomstick. A nearby sign announces that I am standing on the precipice that Tía Casca was pushed from, and I lose my footing. This is where it happened.

And here we have arrived at the forgotten story. This one was harder to uncover, but among the hundreds of references to the morbid legend of the witches of Trasmoz, I found the full account. I wanted to find it for Casca, and for the sake of remembering the stories of the women of the Moncayo: my mother, my grandmother and every other woman who came before and after them.

As it turns out, the story of Tía Casca is no legend. In 2000, the local government began a search for any information about her in the local archives. Their findings confirmed that Tía Casca really did exist and that she was indeed accused of witchcraft on this precipice in July 1860, a full century after the decline of witch hunts in Europe. My grandmother’s grandmother would have been alive at the time.

Tía Casca’s name was Joaquina Bona Sánchez. According to the records, she was born in 1813 and married to Tomás Pérez. The couple had four children. We know of her death because it was certified by Agustín García, parish priest at the church of Trasmoz. According to the certificate, Joaquina Bona died around three in the morning and did not receive her last rites. She was forty-six years old.

It’s hard to imagine that Joaquina Bona, at forty-six, could have looked the way Bécquer describes her—an old hunched woman—although it’s important to remember that life expectancy at the time was around thirty. In all likelihood, Joaquina Bona was a local healer who used her knowledge of herbs and medicinal plants to help others.

We know that people who were accused of witchcraft were often elderly and senile and almost always poor. We know that the overwhelming majority of “witches” who were murdered were women and that they typically didn’t conform to the Christian ideals of the time—faithful wives, mothers and caretakers operating within strict gender roles. We know that these women were often feared because of their knowledge of herbal remedies, which they offered to women to relieve the pains of childbirth and prevent or abort unwanted pregnancies. Women had no real power, but the promise of witchcraft was the promise of power of another kind, one that couldn’t be touched by the men.

The monument to Tía Casca shows her standing upright, a long broomstick held between her legs. I find it moving, a real tribute rather than a frivolous nod to the history of witchcraft in Trasmoz. An acknowledgement that Tía Casca was real and that she was murdered on this hill. I hold the end of her broomstick in my hand and wonder how I never knew about her. But now I understand that these women’s voices have simply been silenced for so long. It is very quiet here, though, and I am glad to see Tía Casca at peace.

As for my mother and I, we get in the car and drive down the hill, leaving Trasmoz behind us. We drive by Veruela Abbey, outside of which a great black cross, symbol of the monastery’s authority, still stands. It is made of Trasmoz marble and is a replica of a previous cross that stood there in times of Bécquer, and at the foot of which he used to sit to seek inspiration.

As we drive back through Vera, we pass the village cemetery.

“If we had the time, I would have gone to see them,” my mother mutters from the backseat.

“Should I turn back?” I ask, ready to drive off the road and shift into reverse.

“No, that’s fine,” my mother says. “We don’t have the time anyway.”

*

I am not sure what I was looking for when I began this search. There were so many things I didn’t know about my history, and yet visiting Trasmoz and shaking hands with Tía Casca felt like coming home. Whatever narrative I was trying to make sense of in my life, I found it stitched on those trails that so many women of mine and previous generations have walked, together or alone.

I think of my mother, when she finally left the village for boarding school in the city. She and my grandmother were so close; what a rip of the flesh it must have been to separate. But my mother had to. Life in that house was unbearable.

I also left the moment I could. I crossed an ocean to be away from my mother and her all-seeing eye. I wanted to be allowed to be weak. I wanted to forget where I came from and to be a new person.

Necessity is the mother of invention, and when your story has been forced upon your body so shapelessly, all you have is a hard, blank slate.

As I returned to the Moncayo, walking side by side with my mother—my grandmother resting not far from us—I understood that she had to forget and reinvent herself too, and that the way she pushed me away was the only way she knew how to keep me close. And I let those old patterns ground down into the soil of the Moncayo, along with everything else that has happened there.

*

When it comes to the history of witchcraft in Trasmoz, it can be hard to separate fact from fiction. The town has such strong popular ties to witchcraft that people congregate in the village every year to celebrate by reenacting the witch hunts and the death of Tía Casca. I’m not sure how to feel about this spectacle; with the distance of history, it is hard for people to grasp that these awful events really happened. This is even more the case when it comes to witch hunts, which have such an air of the supernatural to them that their remembrance elicits more excitement than horror. Yet there is proof that Tía Casca existed and that she suffered a terrible, unjust murder.

When I found out about Tía Casca’s identity, more than anything I wanted to see her face. I wanted to look her in the eyes and take her in, the woman she was, not the witch she became.

I am convinced it must have been magic that led me to Alrededor del mundo, an illustrated magazine from 1899 which I found almost by chance. In the volume, dating from June, a man named Manuel Alhama, alias “Wanderer”, writes about going on a similar quest for truth.

He recounts visiting the village of Trasmoz in search of the family of the famous Tía Casca. There he finds, “in their shacks at the foot of the castle”, the Galgas, a close branch of the same family and direct relations to Casca.

He speaks at length with them, whom he describes as joyful of character (the mother) and pretty and bubbly (the daughter). The two tease him with allusions to balms, stones possessing supernatural qualities, mysterious necklaces and secret recipes.

Wanderer never manages to find out if the Galgas truly are witches, but he does amass great knowledge about the nature of the witchcraft practices that are said to be carried out in these and other Spanish parts. The practice of witchcraft boils down to the preparation of certain unguents according to recipes inherited from others—most often mothers or aunts—and to the use of certain objects, likewise inherited, to which are attributed supernatural powers for the healing of illnesses and the exercise of the will. These unguents bring to mind the “flying salve” of the witches’ sabbath, which women were said to apply to their bodies and which produced hallucinations akin to flying.

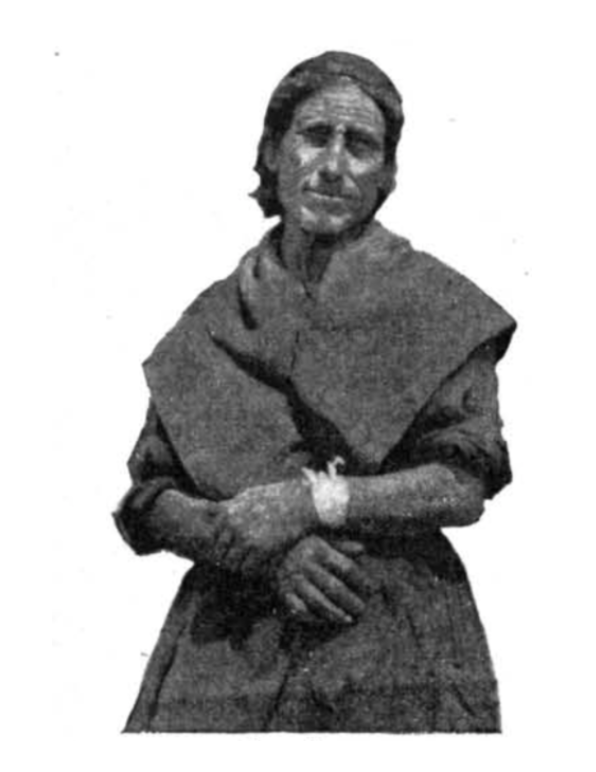

Witch or not, Wanderer does convince Galga, the mother, to allow him to take a photograph of her.

As I turn the page, I lose my breath. The photograph is old and dark, but it is crisp enough that I can see the lines of her face. Here she is, kinswoman of Casca, her face grave and her lips tight. It strikes me as the face of a woman who believes there are certain things better left unsaid.

La Galga