Toxic Femininity and the Witch Trials

Illustration © Kaitlynn Copithorne

‘We are the daughters of the witches you couldn’t burn,’ reads a t-shirt in a crowd. In a woman’s circle, the facilitator at some point announces, ‘men hated women so much, they burnt us.’

There are several problems with these kinds of statements: 1. Most people executed for alleged witchcraft were hung, not burnt. 2. These people were not witches, but scapegoats. 3. While around three-quarters of alleged witches were women in the UK, another one quarter were men. 4. The statement erroneously assumes that the accusers were mainly male, and the victims female. It’s true that most witch finders were men. The 15th-century treatise on witchcraft, the Malleus Maleficarum, was penned by a man (Heinrich Kramer). The following century, James I outlined his fears of witches in his Daemonologie. Such tomes would become the textbooks of the inquisition. But the witch trials were more complicated.

‘Radical feminist interpretations of witchcraft break down when we look closely at the people who accused women of practising sorcery,’ argues Dr Thomas Waters, in his 2019 book Cursed Britain, ‘Half of the imputers were female.’ He notes that some of these were close family – and that females made up almost half of the witnesses at court. Why did women accuse women of something that could get them killed?

Historian Thomas Waters is a regular Cunning Folk contributor and one of the foremost experts on witchcraft. I don’t disagree that our popular understanding of the witch trials is lacking nuance. I don’t think the facts, however, discount a feminist interpretation of this shadow history.

First, let’s be clear: women, globally, still suffer at the hands of men. According to WHO, in 2019, there were around 475,000 victims of homicide worldwide. Human violence is often gendered, with men more likely to kill or inflict violence on women, most commonly women they know. Men, on the other hand, are more likely to be attacked by a male stranger. Femicide occurs in all continents – though it is most frequent in South Africa and Latin America – notably, regions which have, until recently, been under colonial rule – undergoing the same primitive accumulation processes Silvia Federici outlines were integral to the development of capitalism in Europe. I have seen several historians specifically opine that Federici’s work set back our knowledge of the witch trials – a problem is that these critics view her seminal Caliban and the Witch as a history book rather than a political book.

Women suffer at the hands of men. But there is no denying women also had a role in the witch trials, not as passive bystanders but as agents in the destruction of other women. How might this fit with a feminist interpretation of the witch trials? Interviewing Kristen J. Solleé, author of Witches, Sluts, Feminists, in the Fire issue of Cunning Folk back in 2021, the answer, she said, is ‘internalised misogyny.’

I have this tendency to forever imagine what it is to be in minds very different to my own. Imagining I am in the mind of someone tired of these liberal discourses, I think they might think it very tenuous, the way feminists try, always, to make facts fit their worldview. Can’t we admit, they might say, that feminism is no longer relevant – that the role of misogyny in the witch trials was grossly overblown? But Sollée was not grappling with straws. Ample research backs her claims.

For instance, in 2014, sociologists at the University of Michigan looked at slut-shaming among female college students. What they found was that calling a woman a ‘slut’ – a socially stigmatising label – had little to do with that woman’s promiscuity, but that it was directed at people in different social classes, and that it had more to do with asserting one’s own moral ‘purity’ (and presumably, thus desirability?) via ostracising another woman.

What’s interesting (and tragic) is that women weaponise (and often fabricate) against one another, a trait long held as undesirable by men, who have idolised virgins and sought chaste wives. For a long time, a woman’s foremost role was to be a good wife and a mother. During the witch trials, petty neighbourly grievances aside, fears of the natural world and uncertainty presumably intertwined – at least unconsciously – with a scarcity mindset, where other women were rivals. This was, after all, a world of diminishing resources and dwindling common land. The need to become a wife and bear children was often a means of survival – and in many ways it still is.

In spite of progress made in women’s and human rights, there is still a gender pay gap in most regions. Anecdotally, I notice among my peers that most of the women who have ‘made it’ have spouses who work in finance, or otherwise have inherited money. Though women remain at risk of violence and sexual assault, for many of us, gendered discrimination is more likely to look like being patronised or paid less than our male colleagues. There are still gendered inequalities in healthcare, too, with illnesses that impact women like endometriosis and PCOS routinely ignored and their research underfunded. There are still significant hurdles for mothers in the workforce: poor maternity leave payments, in particular for freelance women, who make up a growing proportion of (other-than-maternal) labour. There is the difficulty in returning to ‘professional’ work after the very undervalued labour that is child-rearing. In some parts of the world, people, mostly women, are still accused of witchcraft and violently killed for it.

For women unconcerned by their reproductive value, interwomen rivalry still exists – but now it’s more often about sabotaging another person’s personhood for fear their personal value diminishes one’s own.

Consciously, many of us are supportive of fellow humans, and even more vehemently supporters of fellow women – of ‘sisterhood’. Many of us buy books by women and support women-owned businesses, rallying against centuries of leadership roles belonging to men. Unconsciously, however, many of us still veer into the territory of toxic femininity, devaluing other women socially through gossip, often for their presumed promiscuity or strong opinion. Anecdotally, any woman who has tasted anything that (at least outwardly) looks like success, knows this: under capitalism, people are threatened by another woman’s success: it boils down to questions like Why have they got it, not me? In different professions and situations, the symptoms of toxic femininity can look very different. The age-old fear of the evil eye has endured into the so-called age of rationalism.

These concerns play out in Molly Wise’s directorial debut short film, Trust Thy Sister: rehearsing for a show about the 17th-century witch trials, a group of women fling accusations at each other on and off the stage, the witch trials dynamics seeping between two eras, pre and post enlightenment. The film, which has screened at various film festivals, features Cunning Folk contributor Gabriella Tavini in a lead role. ’The label of “witch” drove people apart in the 17th century,’ Wise tells me, ‘It caused women to turn on each other to save themselves … I want the film to show that toxic competition ultimately leads to downfall, and we can’t make progress until we address it. Community and friendship are powerful tools to make the world a better place.’

Indeed, real progress cannot be made unless we swap a scarcity mindset for an abundance mindset; unless we turn away from self-focus and re-value community. I am not talking about a false community, itself based on neoliberal extraction – what can other powerful women do for me? – but a real one based on community care – how can I help people who do not have what I have? This too can become twisted with ego and performance; it can become twisted with the myth of meritocracy and the now ubiquitous American dream.

Economically and socially excluded from this dream are the poorest and most poorly connected in society – often the working class and marginalised – people who lack the network, resources, and confidence of their peers who went to public schools. Who you know remains more important than talents and skills – rather ubiquitous in the population but seldom given the space or resources to grow.

Practically translating a more liberal value system to life isn’t as simple as it seems. A less toxic breed of sisterhood is not just some woolly sentiment to sloganise, all the while maintaining the status quo, or privileging our own social mobility. Rather, it should be about supporting the people who do not have the same freedoms we have.

Of course, the witch trials weren’t all about toxic sisterhood – sometimes they derived from straight up fear and uncertainty. Today the same forces of scapegoating play out both on the small scale, in families, and on the large scale, in xenophobia and colonial land disputes. What we need is to really cultivate care and trust for others – not an optical solidarity but one rooted in real action.

Toppling down other women is not the answer for improving our own status – nor is it the answer to bridging social inequality. We are more likely to find long-term, satisfying freedom in actively striving to generate abundance, in turn lifting up the people who don’t have things as good as we do, and challenging the systems which make life hard.

But what kind of abundance? And what kind of equality? I could say that we can add more seats to the table, that we can sit together, rise together, and challenge anyone who says we cannot. The problem with this thinking is it implies that our measure of a good life is the very capitalist notion of success as productivity – that the myth of meritocracy is true – that everyone at the table earned their place there – as if the very bottom echelons of the workforce aren’t working extremely hard.

Perhaps we need to rewire our thinking about what constitutes a life well-lived. This is hard for anyone who has tasted the promised fruits of this capitalist age. Under capitalism, we care about the arbitrary flow of symbolic wealth and about individual ‘success’ – fame and wealth promise to bring us closer to the most real earthly paradise. There are other models: for a long time, in so many of our stories and value systems, the highest spire we could achieve was love, a rather ubiquitous resource, and one which cannot be bought or sold.

How to Celebrate the Harvest Moon Festival

Illustration © Kaitlynn Copithorne

We’re fast approaching the Harvest Moon, which this year falls on 29th September. This date holds particular significance for my husband and I as a couple, but it’s also an important festival in the South Korean calendar, where it is called Chuseok, meaning Autumn Eve. The festival is thought to derive from Korean Mugyo or Musok, Korean shamanic practices, which venerated local deities and ancestors. The Harvest Moon is the biggest full moon of the year and appears on the 15th day of the lunar month – and the associated festival celebrates a time of harvest and abundance. Festivities may sound familiar to those who celebrate other harvest festivals including Mabon (a Neo-Pagan festival on the 23rd September, celebrating the Autumn Equinox) and Japan’s Shinto Autumn Equinox Day (also on the 23rd). Chuseok provides an opportunity to celebrate the present by reflecting on the past.

Visit your ancestral hometown, in-person or through writing

Honouring the new yield of crops means reflecting on the year that culminated in this moment. Autumn is a time of nostalgia and reflection and Chuseok is also a time for revisiting the past. Around Chuseok, families in South Korea tend to visit their hometowns – or ancestral hometowns. Each family in the country inherits a book called a Jokbo, which traditionally showed the lineage of all men in a family, but now has been updated to include women, too. From this book, my husband was able to ascertain that his family originates in the ancient capital of the Silla kingdom, Gyeongju. We went to visit the ancient burial mounds – which resembled those Anglo-Saxon barrows I had seen in Europe, in places such as Winterbourne, Dorset – and found the one where his ancestor from over 1000 years ago, a king of the Silla Kingdom, lay to rest. Descending from royalty in South Korea is not unusual – almost two million people belong to this particular clan of Kim – but it is still remarkable to be able to look back at one thousand years of family history and find a connection to the distant past.

This Harvest Moon, we might think about our own origins, whether our childhood homes, or our family roots. We can literally return to a place, or book a trip and visit places important in our family history. Last autumn, we visited Bavaria to trace my mother’s side of the family history – but also to learn more about my prehistoric, Indo-European roots in a valley strewn with caves. It was in the latter that I found more of a sense of collective belonging and meaning, a story I will save for another day.

The idea of returning might be more of a journalling or creative writing prompt. If autumn gives a sense of arrival and completion, it also asks of us questions such as: where did we come from, how did the past shape us, and where are we going now?

2. Make offerings to ancestors

Looking to the past also means thinking about those who came before us. Charye is a Korean ancestral rite that involves the preparation of traditional food – including bibimbap, rice cake soup (also eaten at the Lunar New Year), rice liquor such as soju, rice cakes and soup – to be left at ancestor shrines. The table must be set in a particular way according to family tradition. Preparing the food and carrying out a ritual offering, it is hoped that the ancestors will bless the family for the coming year. You might build a shrine to your ancestors, permanent or temporary, as in the Mexican Day of the Dead alters. You could also practise writing a letter to your ancestors – known or distant – reflecting on how far you and your family have come. Ancestor veneration reminds us of our role in a story far greater than our own. For various reasons, many of us have complicated relationships with our known family that might make ancestor veneration difficult. It might help, instead, to broaden our definition of family to the other friends, animals and loved ones to which we are, at some point in the distant past, connected.

3. Make songpyeon

Korean families eat similar foods to those left to their ancestors on this day. Try making songpyeon, rice cakes shaped like half moons and infused with mugwort or berry juice, stuffed with nutritious ingredients such as chestnut, cinnamon, red beans, mung beans or black sesame. Here is a recipe to make your own. One theory for their shape is that Korean ancestors believed a full moon could only wane, while a half moon can wax and grow – symbolic of coming abundance and prosperity. According to one story, someone who makes beautifully shaped rice cakes will meet a good spouse or give birth to a beautiful baby.

4. Eat Seasonal foods

Asian pears are juicy, crisp and delicious, and typically eaten at this time of year. You can eat what is local and seasonal to you. Here in Britain, apples, pears and blackberries are plentiful at this time of year. Make apple crumble and serve with vegan custard. Forage for mushrooms and herbs. Make pickles, jams, compotes and ferments to last over the colder months. The Korean Vegan by Joanne Lee Molinaro features plenty of recipes for fermented foods, including kimchi and jans, fermented sauces. Traditional Korean cuisine derives from Buddhist mountain cuisine – be inspired by Jeon Kwang’s mindful philosophy towards food and life in volume 3 of Netflix’s The Chef’s Table.

5. Play traditional games (and divine the future)

Come Chuseok and Seollal (Korean Lunar New Year), many families play Yut Nori – a game involving sticks thought to date back to the 7th century. Learn about how to play it here. In the same way that tarot in Europe derived from a playing card game, Yut nori has also been used historically for fortune telling – similar to the throwing of yarrow sticks in I Ching divination. Yut nori sticks are typically made of chestnut or birch, but you can use fallen branches from trees local to you.

6. Learn about Korean folk customs

The probable Shamanic roots of this tradition are most evident, perhaps, in folk customs such as Talchum (mask dance) and ganggangsullae (ancient circle dance). The folk music is drum-heavy and repetitive – the type that encourages a trance state. Though derived from shamanic rituals, in the royal court, and today, these practices have become popular forms of folk entertainment. Typical themes include exorcism rites and parodies of human weaknesses.

7. Walk in nature

Autumn is widely considered the best season in South Korea owing to the milder weather and beautiful colours that paint the woods and mountains yellow, auburn and amber. Take a walk in the forest, mountains or hills, paying attention to the changing scenery, looking for mushrooms, berries and wild herbs. You can use Seek app to identify common plants, but always take care with eating wild food – ensure you know for certain what something is and how to prepare it to prevent toxicity. At this time of year, we love to make elderberry compote or syrup, a delicious hedgerow medicine, rich in vitamin C.

Elderberry syrup recipe

You’ll need:

-Approx 500g (or 2 1/2 cups) of elderberry heads

-400g of light brown sugar

-Juice from one lemon, plus its zest

-1 teaspoon cinnamon or a cinnamon stick

-1 inch fresh minced ginger (optional)

How to prepare

Remove berries from the cyanide-containing stems.

Wash the berries in a sieve.

Add the berries to a pot, covering them with water.

Simmer gently for 15 minutes or until the berries have softened.

Leave to cool and then strain the mixture through a fine sieve.

Pour the strained mixture back into the cleaned saucepan along with the sugar and lemon juice. Cook for 5–10 minutes, or until you have a syrup.

Store the syrup in a sterilised bottle or jar for up to a month. Consume as a cordial with water and ice, in cocktails or mocktails, or with desserts.

8. Practise gratitude

Chuseok is often described as “Korean Thanksgiving” and is about practising gratitude for abundance and family. Like other harvest festivals, Chuseok reminds us of the cycles of nature of which we are part, and the beauty of a year of growing that come harvest produces fruit and grain. Coinciding with the full moon, it speaks to a sense of completion. Among family and friends or in your journal, reflect on what you’re thankful for having reaped in the past year: perhaps it’s a finished project, a new friendship, the birth of a child, or a newly gained skill. Whatever it is, by practising gratitude we remember the value of working towards something, and the importance of doing it all over again after the colder months of going inwards. With each new cycle, we can spiral towards a better present.

The Vampire Issue Playlist

Listen to the Vampire Issue playlist on Spotify. Pre-order a copy of the Vampire issue via our online shop. Illustration © Kaitlynn Copithorne.

Toxic masculinity and the Occult

Illustration © Kaitlynn Copithorne

One of the highlights of my five years in London was volunteering at an occult bookshop in Bloomsbury called Treadwell’s. The shop hardly needs an introduction. Christina Oakley-Harrington, the “Treadwell’s founder and presiding spirit”, has changed the way people view the occult. Formerly a medieval historian at UCL, the curation of this bookshop is perfect. Many of the books are rare or antique; the newer stand up to scholarly scrutiny and are palatable to those of us who also see value, too, in empiricism. The people here know the difference between a witch and a cunning person, two figures many conflate. The events conjure up the image of the salons of times past, where artists and writers gathered to discuss literature and philosophy and exchange ideas.

It was at Treadwell’s I first met historian Professor Ronald Hutton, who taught us via The Triumph of the Moon that Neo-Pagan traditions, including modern Pagan witchcraft, don’t have an interrupted lineage from some ancient traditions of the past. Instead they are valid and creative new religions and spiritual practices, which draw from the past but also innovate. Hutton’s work was inspiring but also freeing. It showed there was no one great and authentic coven or spiritual group that preserved, exclusively, the secret knowledge of the ancient past. There was no one truth more powerful than all others. Instead there were a variety of different schools of thoughts that allowed practitioners to explore their inner and outer worlds. There was the potential for creativity, freedom and a breakdown of the hierarchies and rigid thinking that made so many people leave mainstream religion.

With this in mind, I wonder sometimes about the people who speak loudly and smugly on Twitter about doing “the great work”, while scoffing at others with “less authentic” practices. They are not exclusively on Twitter, nor new. They existed back when I was four years old and living in a retreat centre frequented by many spiritual practitioners. Such people typically belittle people who take up the occult casually, or during certain times of need. They call other people grifters for selling their work, while often promoting their own courses and workshops. They boast about their own powers, while using a language that is full of jargon and acronyms one can only acquire through initiation or very specific reading. So often I see such people dismissing new and creative practices. Too often they are men. I’m not saying this is something done exclusively by men, but it is a trend. Performatively, they might speak about the importance of women’s rights, and fighting against racism. But in practice, their vision is often a very narrow one, that privileges an affluent white male outlook.

Many of these are Crowley fan boys. Or they think there was one grimoire worth paying attention to. Only the rituals and recipes preserved within it were of value. All that came before it: forgettable. All that came after it: a scam. It’s like they found this one recipe for stew from the 16th century and decided it was the master of all recipes and could never be improved upon. And they alone could reproduce it. There was never a greater dish than this one – and if you disagree, your cooking and taste are not just terrible – you’re wrong. They often think folk magic and animism as silly, dismissing it as low magic, a term used to denigrate the magic practised by the common people, and by cunning-folk. They instead aspire to higher magick with loftier goals. After all, they are involved in the great work. They practise ceremonial magic, and gain their knowledge from the finest grimoires. And if you’re lucky, and dedicated, you can learn from them.

Lineage based traditions are interesting. Their authenticity usually hinges on claims that their founders took possession of a secret document that preserved teachings from ancient times. Or, they had a revelation, and transcribed the words of a deity. Usually such lineage claims are disproven by historians, but there is still great appeal in this idea there is, at the centre of this new religion, some deep and ancient truth almost lost to the mists of time. To reveal this concealed knowledge, you must jump through the right hoops, read the right things, and abide by the hierarchical structure. The culture of concealing and revealing knowledge is enticing. It’s like receiving a wrapped present. We want to know what’s inside. It’s what makes Scientologists so keen to pay for auditing, to cross the bridge towards eternal freedom, and on the way learn the secrets of the universe. It’s what compels the spiritually curious to initiate into secret societies.

Many of the ideas at the heart of these traditions are fascinating. As are the tools that can be accrued along the way. But we must remember that they are not the only way towards enlightenment, empowering oneself or gaining creative inspiration. They are usually one man’s way. WB Yeats, Florence Farr, Arthur Machen, Maude Gonne and Aleister Crowley were among many artists involved in the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, a 19th-century secret society founded by freemasons. The society drew from a wealth of ideas popular at the time, borrowing heavily from Judaism, renaissance magic and archeological findings from Ancient Egypt, among other things. Again, fascinating ideas, studied by lots of visionary students. All of these ideas had once existed in different forms, and in different cultural traditions.

This wasn’t the end of the line for these ideas, though. Nor was it the end of the line for the practitioners. Crowley went on to create his own religion, Thelema, cherrypicking from a variety of traditions, including yogic philosophy. WB Yeats was involved with other schools of thoughts around at the time, too, including the Theosophical Society, which was founded by a woman, Helena Blavatsky, and is suspiciously often viewed as more “occult light” than the secret societies created by men. It too drew on beliefs from the East and from Christianity, with the central idea that behind all religions there were essential truths.

In the 20th century, new religions continued to emerge, including Wicca, which Gerald Gardner claimed to be an older religion than it was. He proposed that a coven of witches had survived the witch trials, and continued to gather in the New Forest for the Witches’ sabbath. This fanciful conception story was romantic and pulled at the heartstrings of many who felt the magic of the past had been lost to modernity, but could still be recovered. To this there is a sliver of truth. We can’t forget, though, that the real “witches” were not witches at all, but innocent people tortured into confessions, and then executed.

I have noticed many of the aforementioned male occultists have a tendency to dismiss newer traditions, such as Wicca, for their dubious claims, even when the practices they have dedicated their lives to have similarly dubious conception stories, and borrow from older traditions too. There is no one truth that derives from Atlantis or Ancient Egypt or Babylon. Religion has changed and evolved and recreated itself to meet the demands of current times. Maybe it’s because with Wicca there was no longer such a focus on masculine power, but a recognition of female power. This new religion featured high priests and high priestesses. It included a god but also a goddess. Many of its main proponents, including Doreen Valiente, Margot Adler and Maxine Sanders, were women. That’s not to say there weren’t still gender-based abuses of power within Wicca, but that arguably things were starting to look better for women.

I am not saying here that any tradition is better or more authentic than another. On the contrary, all of these can be of benefit. Lineage claims may repel us or draw us in; whatever they do, they have at their heart good stories that inspire us. New or borrowed, stories are what invite us into new worlds. And thankfully we are learning to tell new stories that we urgently need now – without culturally appropriating – and with or without standardised religion. What I am saying is that we should be wary of he who claims to hold the secret power, while dismissing the practices and beliefs of others. This rigidity doesn’t suggest spiritual enlightenment. Rather, it suggests stagnation, an intolerance towards diversity, and a reluctance to surrender one’s hard earned privilege.

Are we going through a period of Re-enchantment?

Illustration @ Kaitlynn Copithorne

Three years after our Re-enchantment issue, the term Re-enchantment is a buzzword. Every week we’re seeing articles, books, events, and festivals using the word as if it were synonymous with self-improvement through nature, and connecting with childhood wonder. Often, at its most diluted, the term seems quite self-focused. A reminder: if re-enchantment is not about facing the darkness as well as the wonder, it’s not re-enchantment but a dubious self-improvement trend – and something that can be readily packaged, bought and sold. Like so many concepts that have become commodities, we need to tread carefully here.

Lockdown offered many of us the hope the world could be forged anew. Shops closed. For a time even banks. Office work was put on hold. Could this be the end of office work, people asked? Wildlife returned to natural spaces, and, in a climate of food shortages, people took to the fields and parks to forage for nettles, mugwort, yarrow, blackberries, wild garlic, and all manner of seasonal herbs, and roots. People sought self-sufficiency, baking their own bread and learning the old ways of fermenting and pickling foods. Others questioned why they lived in big cities when their prime function – consumerism – was paused. What, they asked, was keeping them there?

There was the idea we could transfigure the bleak world of enforced wage labour, car fumes, and capitalism into something better. For some time before lockdown, having my taste of the London grind, and encountering a variety of the problems many of us encounter on the path of life, I had been thinking about how this something better was something I dreamed of as an idealistic child, growing up in a retreat centre in the rural West Country. When we are young, arguably, we are more deeply connected to our principles. The world then was a living, breathing entity, and all its inhabitants were worthy of our protection. Children are deeply sensitive and perceptive in ways few adults are. In the words of JM Coetzee’s Elizabeth Costello: "It takes but one glance into a slaughterhouse to turn a child into a lifelong vegetarian."

Max Weber held the view that modernity is “characterised by a progressive disenchantment of the world”. This, in short, refers to the devaluation of religion and spirituality. I think growing up follows this pattern too. Once our ancestors believed in fairies, spirits, spirits of place, and gods. They asked trees for permission before plucking their fruits. They built temples on sights where they encountered good omens. Now we consume and develop with little consideration for Feng shui or appeasing the local deities. As children, we brewed potions from flowers and spoke with animals, and saw faces in trees. We might have believed in fairies – or at least the tooth fairy. Some of us believed that each December, a bearded generous man rode through the sky in a reindeer-driven sleigh.

Scholars still debate the meaning and validity of Re-enchantment. In The Re-enchantment of the World: Secular Magic in a Rational Age, for instance, authors Joshua Landy and Michael Saler argue that there has always been a counter-tendency towards magic, challenging the view that modernity is “disenchanted.” Yet Weber’s words still spark resonance with those of us who have seen the loss of the commons, which Silvia Federici writes about both in Re-enchanting the World: Feminism and the Politics of the Commons and in her seminal Caliban and the Witch. Even today people resist the loss of rights to roam or to wild camp – just this year Dartmoor banned wild camping, the last place to allow it in England. Re-enchantment also strikes a chord with those of us who have lost freedom and bodily autonomy to an ever more oppressive state. Disenchantment is by this definition a violent severance from our knowledge of the natural world. Real or imagined, gone are the days of King Arthur and Odysseus, when heroes set out into the wilderness and encountered mythical beasts, witches, and strange places with distinct spirits.

Of course, we ought not glamorise the magic of the past without remembering the darkness. Among the fairies of the past dwelled darker entities, who weren’t to be messed with. As a child, I was terrified of the darkness, of what dwelled in the secret room that lay through my wardrobe in that dusty old house, of the shadows that moved between the trees. Magic is a wondrous and terrifying thing. To believe in enchantment means to believe in the power of will, the miraculous, and a world of spirits, spectres, fairies, or otherworldly entities; it can entail the sense of wonder one feels standing upon a mountaintop at dawn or dusk, watching a sunset or encountering synchronicities. But it also means confronting the bone-shaking fear that others have cursed us, the evil eye, the inevitability of death, and our limited understanding of the world even with our miraculous science. It’s also in the chaos of pandemonium, meeting Pan, god of the wilds, in the forest; spotting ill omens such as a chance encounter with the Wild Hunt in the most treacherous forests, whose apparition foretold of war, plague, or no good thing. We cannot have light without dark. Re-enchantment requires negotiation and respect for the sacred. We cannot take everything without giving back.

Can you sell re-enchantment? You can sell anything. We’d do well to remember what happened to mindfulness, and how the Ancient Indian practice of yoga has been appropriated to make workers more productive and resilient. Mindfulness in truth was much more than McMindfulness. It was about slowing down, paying attention, and tuning into the atman – the universal self. In turn, the practitioner could find relief in the longevity of nature, up against the brevity of our own lives.

Capitalism is a shapeshifting entity that does its best to make us feel safe and cared for. We have seen the same dilution of other traditions or practices over the years. High street shops sell spell and ritual kits, often featuring the precious herbs of indigenous people, with no acknowledgment. And the market has recognised the brand potential of certain practices like walking in the woods and swimming in the sea or river, with forest bathing and wild swimming becoming the terms du jour. You may have heard of Bhastrika pranayama – a type of rapid and forceful breathing that exists within the yogic tradition and creates heat. Or the tradition of immersing oneself in ice-cold water – common in Finnish, Russian, and Kazakh cultures – among others. Such practices have been combined into the Wim Hof technique, which people pay thousands for. Even “the life-changing art of tidying up” has become a commodity.

We have to keep paying attention to the beauty of the world. But opening our wallets for expensive spiritual or self-help workshops will only take us so far. You don’t need to pay for a fancy course – independent makers such as ourselves are grateful when you support our work by attending – and many skills require expertise, such as the craft of writing, herbalism, and meditation. But you needn’t spend hundreds of pounds when many of these things can be learned from reading, spiritual practice, and more humble practitioners who don’t position themselves as gurus or charge the world. Honestly, for re-enchantment, you don’t need a book, course or manual. As The Book of Molfars concludes: “you are the book.” We do need to pay attention to what exists in the world around us. Only then will we know what is at stake.

For real self-care, we also need world care. Our mental health hinges upon things like personal freedom, reliable shelter, good quality food, offline community, and access to nature. This can be simulated in a monetised course, but we need these things long-term. Perhaps we need now an apocalyptic type of witchcraft, the type Peter Grey calls for in his urgent manifesto:

“Witchcraft is the recourse of the dispossessed,

the powerless, the hungry and the abused.

It gives heart and tongue to stones and trees.

It wears the rough skin of beasts.

It turns on a civilisation that knows the

price of everything and the value of nothing.”

We don’t need the market standing in for our very basic fundamental human rights. We need to take back the rights to our lives. In Revolutionary Road, author Richard Yates asked, “Are artists and writers the only people entitled to their own lives?” I think so – alongside the ultra-rich – though this isn’t right. I wish we too had the right to lead lives like cats, moving with the sun, sleeping, eating, and roaming free. When I was little, I use to climb down cliffs and scramble through the wild forest and swim in the sea. I didn’t think of it as wild swimming. I was swimming, walking, climbing, and exploring. I was living.

Rather than re-enchantment, I think we’re now going through a period of intense disenchantment. Not necessarily in the sense of religion. There has been a rise, in recent years, of Neo-Paganism, and other new religions. There has been a decline in Christianity but a rise in Islam. But we have returned again to incessant self-focus and we commodify everything, from places and fruits of the earth to intangible ideas. We’ve returned to nihilistic consumerism and, many of us, to the obligatory 9 - 5; while a gift for some, not all are well-suited to those hours or that rigidity. Many of us hold collective trauma.

What’s more, we’re in the midst of an intense cost of living crisis. Many are struggling to eat or heat their homes. There has been a return to a Dickensian kind of philanthropy, when most developed countries are rich enough to provide welfare to those in need, here and elsewhere. Every week people in my community come forward and share they haven’t enough to eat, and have to rely on the kindness of strangers – despite living in a rich country with the resources to provide. War is drawing nearer. Peace seems far-off. The threat of nuclear war renders the bleakest and most apocalyptic visions of the future feasible. Faced with war and all the problems that have emerged since we’ve left our homes, re-enchantment seems at best a pipe dream – at its worst, privileged.

The idea still has room to grow, but should never exclude activism, taking responsibility for our part in the problem, and seeking to make it right – and never for the cultural capital that comes from performative activism but a real collective desire to change the world.

Re-enchantment is not a commodity. Nor a short-lived soothing balm for the soul. Re-enchantment is not something that can be affixed to “I” but “we”. Re-enchantment is not sitting in a field and covering our ears with our hands. To cite the Hookland Guide, “Re-enchantment is Resistance.” If re-enchantment is not resistance, it’s at risk of fuelling delusion and complacency, the very things that got us where we are now. Resistance requires facing up to our own responsibility, doing shadow work, and self-sacrifice. It requires us to look inwards and outward. What would make the world better? I think this is as important as thinking about what would make us feel better.

Diane Purkiss is a professor of English Literature at Oxford University, the author of numerous books on witchcraft and feminism, and a regular contributor to Cunning Folk. “I'm really interested in the idea of re-enchantment,” she tells me, “but I strongly agree that it can easily be turned into a way to brush darkness under the rug. It seems to me especially relevant at the moment to ponder the ongoing cultural raids on Indigenous cultures as examples of Western subjects turning everything into an opportunity for self-development (the majestic words of Bo Burnham) – and I also agree that with that goes to risk of paying no attention to war, or to the way that the mental health crisis we continue to face is connected with the ugliest aspects of late capitalism. An alternative way to think about re-enchantment might be to see it as a way for deracinated Western people to reconnect not just with the natural world that they are otherwise blind to destroying, but also perhaps with one another.”

On the topic of how we might go about re-enchanting ourselves, Purkiss says: “it seems to me very important for [re-enchantment] not to be a marketing opportunity to do with buying candles … It seems to me that the best way is through stories, and through above all listening to stories that connect with place. Recognising ourselves through stories without seeking to appropriate them is challenging, but I think it's what we must do.”

Activism, changing our lifestyles, and connecting with stories and the spirits of time and place will ultimately provide tools for wrestling against capitalism. We need to listen without claiming, and learn to appreciate while resisting the temptation to rewrite or possess. The rough beast of capitalism tries hard to remodel itself so that it looks like it has our best interests at heart – but we’d do well to remember it does not. Re-enchantment is as political as it is spiritual; it means finding meaning again in a world we’ve reduced to nothing. When we believe in something we fight for it. In turn, we might collectively veer away from the terrifying alternative endpoint to which we seem to be headed.

The Earth Issue Playlist

Listen to the Earth Issue playlist on Spotify. Pre-order a copy of the Earth issue via our online shop. Illustration © Kaitlynn Copithorne.

The Air Issue

Cover illustration by Katy Horan.

Air was the theme we were always a little wary of. What could be said of the spaces between things? But as we worked through this issue, many of us found ourselves to be disproportionately airy, or “away with the fairies”, and often in need of grounding and planting roots, balanced by good food, crafts, dancing, yoga and other embodiment practices. As a consequence, we loved how this issue turned out— strewn with melancholy, grief, and wonder at the mysterious world that lies just out of sight. Its conception felt at once personal and universal, and, as always, we’re proud of the writings and artwork featured within.

Who made the Air issue?

Our magazine is always a collaboration between writers, artists, and our small team artists and writers. Some 50 people or more come together to make it happen. Edited by Elizabeth Kim and Eva Clifford, art direction is from Kaitlynn Copithorne and photo editing from Michael Vince Kim. The magazine is designed by Kayleigh Pullinger and sub-edited by Michelle Harrison.

How to find the Air issue?

As with all indie publisher, note that the best way of supporting us is by buying direct via our website.

Stockists

We also love supporting independent bookshops. We will keep updating this list. Note: not all will sell this online—it’s worth dropping them an email to see if they have it in stock.

UK

London

Bath

Leeds

Colours May Vary

Edinburgh

Portugal

US

If you are a book buyer and interested in getting in touch with us about trade discounts, please contact us at cunningfolkmagazine@gmail.com.

The Air Issue Playlist

Listen to the Air Issue playlist on Spotify. Pre-order a copy of the Air issue via our online shop. Illustration © Kaitlynn Copithorne.

How to Celebrate the Spring Equinox

Illustration © Kaitlynn Copithorne

Can you call it Ostara/Eostre?

Historians have “debunked” the history of Ostara, linking her to Easter eggs and bunnies. This doesn’t, however, mean that you can’t celebrate her. All religions were once new and all stories started somewhere. Myths are seldom literal, anyway—but speak to deeper truths—things we often need now. As Professor Ronald Hutton articulates in his book The Triumph of the Moon, maybe such figures that appear suddenly in the collective unconscious—whether we call them archetypes or deities—come into being when we have need of them. Much in modern Pagan belief systems speaks to our longing to rewild and find some harmony with nature. Polytheistic pantheons such as Hinduism often express the idea that all deities are but different aspects or faces of the one—and different ways of reaching the universal. These will change regionally and in a lifetime, depending on changing needs. So there is no need to abandon Ostara, if she means something to you. But there is another side to this, too: the beauty of knowing the history behind such figures—or of learning about the ingenuity of human creativity—is that we do not dogmatically have to venerate anything or anyone who does not connect with us. What are organised religions if not a cherry-picking of different stories from folklore, brought together into a standard? We’ll know if something or someone in the world calls out to us. Robert Graves believed “true poetry” was “always the invocation of the white goddess, and the realm in which she presides.” We may feel it when our skin is goose pimpled and our eyes start to water. To you this response might be the result of an invocation of a wood nymph, a familiar spirit animal, a whale god, an ancestral spirit, a character from a story. If a story, poem or celebration—new or old—doesn’t instil in you wonder, you don’t have to observe it. You may wish to think about what it is about this time of year that inspires or moves you. We can revisit old stories and tell new stories, and create new rituals, respecting where we’ve been and where we’re going, adding to our personal and collective repertoire of symbols.

Read about different celebrations of the Spring Equinox

The spring equinox is an astronomical event and its celebration has historical precedent. In the Northern Hemisphere, March 20 signals the end of winter and the beginning of spring. For one day, most places will see 12 hours of night and 12 hours of darkness. In Ancient Rome, Hilaria was celebrated on March 20, a festival to honour the goddess of Cybele, associated with fertility, wild animals, mountains and city walls. The Babylonian calendar began with the first new moon after the March equinox, while today the Persian, or Iranian, and Hindu calendar begin on March 21. That the new year should start when the world is reborn seems apter than our current date in midwinter.

Spring cleaning

Spring, like the new moon, is often envisioned as a time for new possibilities. This can mean cleaning the house, your computer files, getting a few tasks off your list before you embark on something new. There can be a bit of melancholy and apprehension at the prospect of setting off on this journey. There’s a sense of liminality and fear at the prospect of being thrust back into the heady pulse of living. Kenneth Grahame in The Wind in the Willows expresses it well: ’The Mole had been working very hard all the morning, spring-cleaning his little home. First with brooms, then with dusters; then on ladders and steps and chairs, with a brush and a pail of whitewash; till he had dust in his throat and eyes, and splashes of whitewash all over his black fur, and an aching back and weary arms. Spring was moving in the air above and in the earth below and around him, penetrating even his dark and lowly little house with its spirit of divine discontent and longing.’ So too does Edna St. Vincent in her beautifully dark poem “Spring”: To what purpose, April, do you return again? / Beauty is not enough … It is not enough that yearly, down this hill, / April / Comes like an idiot, babbling and strewing flowers.”

Learn the uses and lore behind flowers in bloom

The flowers are already in bloom again here. In particular our city parks are awash with daffodils and crocuses, piercing through the earth where so recently there was snow. Different commentators and traditions may assign different folkloric meanings to plants, but their medicinal uses may be universal. Scott Cunningham tells us that daffodils are lucky and associated with love; placing them in the bedroom, he says, can help with fertility. He says that crocuses also attract love, but can also help us capture thieves: “Burn crocus along with album in a censer, and you may see the vision of a thief who has robbed you. This was done in Ancient Egypt.” Unsourced as this compendium is, we cannot ascertain its reliability. Read about the Victorian language of flowers, or floriography, and see how you might communicate a message through thoughtful floristry. The Complete Language of Flowers by Theresa Dietz may prove a helpful resource.

Eat seasonal foods

Here in the UK, Asparagus and artichokes are in season, and delicious simply served with olive oil, sea salt and if you like, lemon. Rhubarb can be stewed with ginger and sugar and served with homemade custard or on porridge. Wild garlic is in season and can be made into a delicious pesto — Maggie Eliana wrote a piece for our Water issue titled ‘Along the Backwater: Plants of Riverbanks and Waterscapes’, where she noted the uses of willows and watercress, among other plants. Here is her wild garlic pesto recipe, from this article:

Wild Garlic Pesto Recipe

Ingredients:

One large handful of wild garlic leaves

½ cup of pine nuts, sunflower seeds, or pumpkin seeds

¼ cup olive oil or sunflower oil

3 tbsp nutritional yeast

Zest of one lemon

Pinch of salt and pepper

Pinch of chilli flakes (optional)

Method:

Rinse the wild garlic.

Optional: Toast the nuts or seeds.

Blend all the ingredients in a food processor. You can also use a pestle and mortar for a more ‘back-to-basics’ approach.

Spread on toast, use as a pasta sauce, dollop into soup or on top of risotto; the options are endless.

Cultivate your garden

“Il faut cultiver notre jardin” — or “We need to cultivate our garden” ends Voltaire’s Candide. The characters have travelled the entire world and experienced the absolute worst of the humankind. Returning to their garden, they are able to shield themselves from the worst of it while cultivating the best of it, making in this hell a little slither of paradise; some consider this a retreat from the world, but others, yet, a commitment to improving the world through a kind of constructive pessimism. Like Candide, and perhaps Voltaire, go ahead and cultivate your garden, real or metaphorical or both: sow seeds that will grow into beautiful flowers and into foods that can be eaten, gifted to others or traded. Leave seeds out for the birds who at this time of year have young hatching from eggs. Perhaps much in this world can’t be redeemed, but here is a corner of the world you can make better, starting from today.

The Fire Issue Playlist

Listen to the Fire Issue playlist on Spotify. Pre-order the Fire Issue via our online shop.

The Feminine Magic of Mushrooms

Image © Alexandra Dvornikova

Throughout literature, the mushroom, mycelia, and fungi have always been a source of great magic and inspiration. The beauty, practicality, and potential peril of mushrooms have caught the imagination of naturalists and writers for centuries. Think of the Amanita muscaria from Alice in Wonderland, the magical mushroom that allows Alice to change size. Or of Prospero in The Tempest, who says of fairies and elves: “By moonshine do the green sour ringlets make, Where of the ewe not bites; and you whose pastime is to make midnight mushrooms.”

The sudden popularity of the mushroom as a modern-day magical emblem is hardly new. It is, rather, a renewed interest in a symbol that has long formed the basis of many of our greatest stories. In particular, the mushroom has been depicted in some of the oldest religious texts known to man. In the Vedas, compiled in northern India between 1500-1200 B.C, “soma” was referenced as a potion drunk by deities, blessing them with wonderful powers. Likewise, the mushroom has found a particular synonymy with medieval Christian and religious artworks. A Romanesque Fresco in the Abbaye de Plaincourault in Indre, France, appears to depict Eve’s temptation by an Amanita muscaria mushroom instead of an apple, with a sinister serpent coiled around it.

The symbol of the mushroom in stories has always been more than just “a food,” and more recently, the mushroom has captured the contemporary imagination through the popularity of aesthetics like goblincore. Playing upon the fantasy of rural domesticity and escapism from the monotony of day-to-day life, the mushroom is now evocative of something far more than just whimsical and experimental than we could have ever conceived. Seen across platforms like TikTok, Pinterest, and Instagram, there has been an unequivocal cultural longing for all things whimsical and folkloric. And we might have books to thank for its renaissance in popular culture.

The emergence of Victorian fairy-centric literature would be embedded with imagery of rusticism, paganism, and the otherworldly, and in these works, the mystique of the mushroom was a recurring motif. Deceptively aimed at children, such novels, under the guise of “innocence”, could explore more adult themes through the reimagining of the countryside, now framed as a site of sensual and erotic exploration and a kind of psychedelic re-enchantment. At the core of it all lies the visionary power of nature. Plants, flowers, and fungi were integral to the rich lore of these newly imagined worlds in which forest folk would dart between toadstools and faerie rings. Not only did these images help weave a rich tapestry of mythical storytelling in the 19th century, but the mushroom also became emblematic of otherworldliness itself through its potentially psychoactive properties, ornate design, and synonymy with magic.

Beyond the literary realm, the mushroom has been long linked to femininity, witchcraft, and old magic. Ecofeminist theory of the late 1970s began to address the parallels and similarities between both female and environmental oppression and exploitation, and also links between the maternal qualities of women and nature due to their traditional role as nurturers and caregivers. In an age of gender-fluidity and self-expression, the mushroom is symbolically more important than ever with its potentially infinite number of sexual variants. But the connection between femininity and the mushroom isn’t limited to a purely symbolic value; the tremella fuciformis fungi is notable for its medicinal properties that target mostly feminine ailments, such as cervical and breast cancers.

Another lesson can be taken from the mycelium, who co-exist through their density of connections with one another. In an article for the BBC, Nic Fleming writes, “We now know that these threads act as a kind of underground internet, linking the roots of different plants”. Similarly, in Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds and Shape Our Futures, Merlin Sheldrake explores how the endlessly surprising organisms feed nearly all living systems. Alongside the potentially psychedelic and mythical emblems of the mushroom, through these communication channels, the mycelium has come to represent something far deeper about the interconnectedness of humanity and our ecosystem; the vitality of one another for our own sustenance.

With this sentiment in mind, it is unsurprisingly that fungi would have been such an inspiration to the likes of Sylvia Plath and Emily Dickinson. Dickinson projects the entirety of ecological and folkloric potential onto the humble fungus; “Had Nature any supple Face / Or could she one contemn / Had Nature an Apostate - / That Mushroom - it is Him!”. She dubs the mushroom the “elf of plants”, likely due to the reproductive spore’s variety of sizes, shapes, and colours. Similarly, Plath’s poem “Mushrooms” certainly doesn’t shy away from the gendered connotations of mycelium:“we are shelves, we are Tables, we are meek, We are edible, Nudgers and shovers In spite of ourselves. Our kind multiplies: We shall by morning Inherit the earth. Our foot's in the door.” With Plath’s description of fungi as “meek”, she evokes connotations of the perceived fragility and submissive nature of femininity. The inconspicuous little mushroom is often misjudged. Though small its flavour and aroma can be potent—it can potentially be toxic. Like women, mushrooms often have their power underestimated.

In his The Interpretation of Dreams, Sigmund Freud made the case for the feminine connotations of ecology, mushrooms, and mycelia. What later formed part of the basis for ecofeminist scholarship, Freudian psychoanalysis drew conceptual links between gynocentric values and ecological consciousness. Yet despite the mushroom’s deep synonymy with fantastical Victorian and 20th-century literature, 2021 has seen the mushroom find a cultural resurgence. Perhaps the renewed popularity for the mushroom, as a source of creative inspiration, is down to the resurgence in climate crisis activism, through figures like Greta Thunberg, arguably the face of the climate crisis; the battle for ecological autonomy has always been deeply feminised—both within the literary canon and outside of it.

Although ecofeminism was only established as an academic school of thought in the late 20th century, the origins of ecocentric environmentalism date back to the periods of American transcendentalist and European Romanticism. Valuing nature above culture persisted throughout the Romantic period, notably in William Blake’s poetry which sought to forge links between the colonisation of American soil and the treatment of women. From taking advantage of their naturally fertile qualities to the systematic attempts from the patriarchy to claim ownership of what is not rightfully theirs, the parallels between the exploitation of women and nature are bountiful.

Perhaps there is hope to be found in the contemporary treatment of the mushroom. Today, it seems the mushroom is an emblem of endless potential and creativity. The mushroom offers a sense of magic in the everyday, a symbol of interconnectedness where we are so often confronted with signs of environmental destruction. It is no wonder that mushrooms have continued to inspire writers over the decades; may the humble ‘shroom continue to do so.

A Census of Hazelnuts

Illustration © Liam Lefr

The lockdown has eased a little and I am on the deck of a ferry rumbling across the Solent to the Isle of Wight, under a pale, spring sun. I grew up on the island so this is a trip home, but it is also something of a magical quest.

Despite glorious views from the deck, my thoughts are mainly with a medieval woman called Julian. She was a mystic and anchorite who lived for years sequestered alone in a cell attached to a church in Norwich. At some point in her life she became gravely ill and expected to die and had a series of “shewings”—or visions from God. On one occasion:

“He showed me something small, no bigger than a hazelnut, lying in the palm of my hand, as it seemed to me, and it was as round as a ball.”

She asked what it was, and she was told it was “all that is made”. She had the whole cosmos in her hand, and she marvelled that something so immense could be contained in so small a shell. She was told it was sustained by the love of God. She recorded her shewings in her book Revelations of Divine Love. Over six hundred years later I read her account of that hazelnut when I was a teenager and was entranced by it. I am thinking about her today because I am on a quest to find some very unusual hazelnuts.

I have been drawn to hazelnuts for years, but it wasn’t until I was lighting candles one day, at my ancestor altar, that I realised the extent of this attraction. The tabletop around the candles was covered with them. I started a census: how many were there? Where had I picked them up? What were their stories?

*

There were four half-shells. You can tell what kind of creature has eaten the nut by the way they have opened the shell. By far the most common is the cleanly sliced half-shell. This is the work of Squirrels. There is a place in the woods where I have made a circle to do magic. I dug these half-shells from the dirt ground inside my circle and I have used them often over the years for divination. Geomancy is a form of divination that relies on figures created randomly from ones and twos, for example, some people toss coins. Half hazelnuts can be cast in the same way because they only land up or down.

There were a number of nuts I have burned with a hot needle. Some had sigils on which I have since buried in that same earth to decay the next time I visited the forest. On some I had written in tiny burned letters “Mother Julian. Pray for Us”. These I give as gifts to those who might need or appreciate them.

There were two fat and gloriously dark brown nuts that I found half in the ground of a disused holloway in the lee of the South Downs. A holloway is a path so ancient that feet and wheels have gouged it down into the surrounding country, sometimes the sides are twenty feet high and more, and trees grow on top of that, so that meeting above it, a green tunnel is created. The holloway I found was only a hundred metres long and it was clear no one had used it for decades. The soil was softer than feathers and the air was green and secret. When I stopped to sit with the place for a while, I found these nuts. They slipped into a pocket and then to the front of my altar at home.

Two nuts were almost black. On a fearsomely stormy day in Cornwall my partner and I battled along a beach in a small cove and from the weed and detritus at the high tide line came two hazelnuts. Southern Cornwall is famous for its tree-lined rivers that meander out to sea. These nuts had clearly fallen into a river and been carried out and back again. They are the darkest, shiniest, hardest nuts in this census.

There is another nut which was found on a different shoreline. This one is almost grey, its shiny surface is gone. The exposed ridges are deep and clear. It is the nut equivalent of a leaf-skeleton.

*

All these nuts have come to me. Placing them in front of the ancestor altar just seemed the right thing to do. Each one is a little bit of magic. Today though, disembarking from the ferry, I am setting off to find hazelnuts deliberately for the first time. The west of the Isle of Wight is a far cry from the bucket-and-spade image of the seaside towns on the east and north of the island. High cliffs, wild Atlantic seas and deep chines dominate the coastal landscape here. An hour from the ferry is Compton Bay, famous for its dinosaur footprints and fossils from many millions of years ago. I am after something ancient but not quite so ancient.

Hazel as a species is one our oldest companions in northern Europe. As the ice advanced and retreated over millennia humans and hazel moved with it. There is archaeological evidence back to the Mesolithic of humans gathering hazelnuts for food in vast quantities. It is thought Hazel might have been one of the very first species to be cultivated. No wonder it felt right to place them in front of the ancestors. At Compton Bay high in the eroding cliff face is a layer of gravel, an ancient riverbed, 8,000 years old. Pieces of wood from trees that overhung that river and fell in are occasionally exposed and tumble to the beach, partially fossilised. Among those remains are often found, of course, hazelnuts.

The breadth of the folklore about hazel surely reflects its long companionship with human beings. Best known, perhaps, is the hazel wand. Throughout European magic, the use of a hazel wand is widespread: it is often procured at dawn, on Midsummer’s Eve, cut with one blow, from ‘virgin’ growth; sometimes it is cut behind one’s back, to be the length of the forearm. Different source texts include different combinations of these requirements. The variety, historically, means that today we can take a wide view and understand these as expressions of an underlying ritual structure surrounding the creation of a hazel wand. It’s like learning the grammar underlying a language.

In the UK, hazel has folkloric associations with Faeries; in her book Under the Witching Tree, Corrine Boyer presents two spells, one from the 15th and one from the 17th century which use hazel sticks and hazel buds respectively to help the witch see the little people. Hazel is also helpful with weather magic: contemporary reports of witch trials in Europe detail the calling up of storms by beating water with hazel rods. There is a connection with lightning; there was a widespread belief that hazel trees were never struck by lightning, and therefore it followed that hazel was good for protecting the house against a strike. In various parts of the UK and Europe, a hazel rod, a cross of hazel, or a hazel rod driven through the body of a Robin were used to ward off lightning from houses or crops. Snakes too have woven their story into that of the hazel: in Ireland there was a legend that St Patrick drove out the snakes with a hazel switch; there are medieval and early modern charms against snakes and their bites, that use hazel, from places as far apart as Sweden, the Balkans, the Black Forest and the West Country. Tellingly, there isn’t much in the herbals about hazel; probably this is because, like potatoes and carrots, the primary relationship we have with this plant is as food.

The thing that draws me most to these tiny, humble little nuts is this long standing relationship with humans. It is something of that depth of time that I am trying to capture through my quest on the Isle of Wight. It was 8000 years ago that this river ran, that these hazelnuts fell, and also that the glaciers in Northern England and Scotland melted. The glacial meltwater flooded the low-lying woodland between what is now the Isle of Wight and the mainland and created The Solent. These semi-fossilised hazelnuts share their time with that huge flooding event. Is this why, for centuries these humble remnants of that time have been known to islanders as Noah’s Nuts? Maybe, except that the first reference I can find to that name comes from the 1790s. This is long before we had an understanding of ice-ages, glaciation and the flooding that would have created the Isle of Wight. It is extremely unlikely that there is continuity of understanding between islanders today and those who lived 8000 year before, but our human ancestors and other species, like the hazel tree, have travelled some very long lines through time and those lines come together and cross and merge in all kinds of ways. It is those lines that create story and magic. It is also those lines which lead directly to me on my knees, with the sun on my back at the bottom of a cliff searching for 8000-year-old hazelnuts. Did I find any? Not this time. But I will be back.

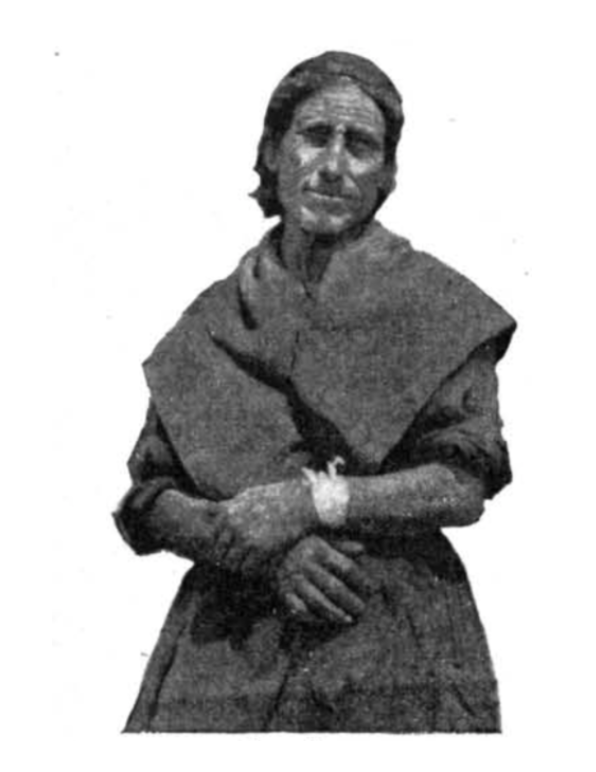

Doreen Valiente: Mother of Modern Witchcraft

Illustration © Kaitlynn Copithorne

In October 1964, around fifty witches gathered at a dinner held by the newly-formed Witchcraft Research Association. Although its life span would prove short, the Association aimed to serve as a unifying force in the increasingly fractious and factional world of Wicca. The organisation’s president at this time—Doreen Valiente—hoped that the Association might eventually become the “United Nations of the Craft”:

‘What we need now, more than anything, is for people of spiritual vision to combine together... if only people in the occult world devoted as much time and energy to positive constructive work as they do to denouncing and denigrating each other, their spiritual contribution to the world would be enormous!’

This speech, in all of its rousing clarity, summarised so much of Valiente’s approach to witchcraft and magic. Often lauded as the “mother of modern witchcraft”, Valiente’s attitude was one of inclusivity, but also discernment. As a writer of books, poetry and Wiccan liturgy, she ensured her words and offerings were accessible to all. Yet behind her warm tone of guidance, there was a sharp, shrewd researcher and fierce believer in authenticity, integrity, and social justice.

Born in Surrey, 1922, to parents who were, in her own words, “brought up Chapel”, Valiente would later laugh off claims that she was in fact the illegitimate child of the Great Beast, occultist Aleister Crowley. Whilst the reality—being the daughter of a land surveyor and architect—might seem less interesting, young Valiente’s experiences were far from ordinary. As an adult, she reminisced about her mystical experiences and encounters with the uncanny as a child, and according to her biographer Philip Heselton, she was making poppets and had grown into an accomplished herbalist by her teens.

Valiente’s work during the Second World War is thought to have been of a sensitive nature, as she was most likely based at Bletchley Park—the code-breaking centre of the Allied Forces. After a brief marriage which ended in her husband’s loss at sea, she moved to Bournemouth with her second husband, Casimiro Valiente. It is on that stretch of England’s southern coast that her interest in the occult spiralled. Trawling local public libraries for esoteric texts, Doreen Valiente began her studies in earnest; from Spiritualism to Theosophy, she gobbled up everything she could lay her hands on. Never one to forego the practical aspects of learning, Valiente attended a Spiritualist church (at which she read aloud a Crowley text she had discovered), as well as joining a local parlour group that discussed esoteric matters. Around this time she also began practising ceremonial magic with an artist friend who went by the magical name “Zerki”, and together they would work rituals in his flat which were influenced by the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. Valiente chose her own, John Dee-inspired magical name at this time too—she would go by “Ameth”.

After years of intensive magical study and research, Valiente entered into a correspondence that would lay the foundations for her later renown as a witch. A keen collector of newspaper articles about occult matters of all sorts, in 1952 she came across a piece in Illustrated magazine titled Witchcraft in Britain, which mentioned a coven of British witches who had performed a ritual in the New Forest during 1940, attempting to prevent Hitler from invading Britain. In 1951 the last vestiges of the Witchcraft Act, outlawing such occult actions, had been repealed, and Gerald Gardner—the “resident witch” of a museum of magic on the Isle of Man—had started courting media coverage, including via the article discovered by Valiente. In her book The Rebirth of Witchcraft, she recalls feeling incredibly excited by Gardner’s references to witchcraft as being “fun”, which seemed a very novel idea at the time. Writing to the museum’s founder, Cecil Williamson, Valiente’s letter was answered by Gardner, and their correspondence began. Gardner had been initiated into the New Forest coven by a witch known as “Dafo”, and it was at Dafo’s house that Valiente met with him for the first time. She describes this significant event in one of her books:

“We seemed to take an immediate liking to each other...One felt that he had seen for horizons and encountered strange things; and yet there was a sense of humour about him, and a youthfulness, in spite of his silver hair.”

Valiente as initiated into Gardner’’s Bricket Wood coven a year later at Stonehenge (without the knowledge of her husband, who remained a lifelong sceptic). Notably, hinting at the import she gave to magical provenance, Valiente recognised that many of Gardner’s words and actions at her initiation bore a resemblance to those of Crowley and the folklorist Charles Godfrey Leland. Over time, Valiente grew increasingly sceptical with regards to Gardner’s “ancient” sources, criticising his overuse of Crowley’s texts. Eventually, according to Valiente, Gardner’s response to her criticisms was along the lines of “if you think you can do better, get on with it!” Never one to shy away from a challenge, she did, and went on to rewrite many of Gardner’s rituals to great effect. Indeed, Professor Ronald Hutton notes that Valiente’s words for the White Moon Charge “gave Wicca a theology as well as its finest piece of liturgy”.

Gardner’s hunger for publicity grew, and with increasing press coverage came more coven members, but also greater media sensationalism and public ire. Valiente, by now the coven’s High Priestess, disapproved—preferring Wicca to make itself known through its books rather than being filtered through the lenses of journalists keen for a throwaway headline. Valiente broke with Gerald’s coven, founding a new one with her allies which would practice Gardnerian Wicca without being beholden to its namesake. She believed there was work to be done in finding the real “Old Ways”; the pre-Christian pagan rites that promised to be more authentic than Gardner’s patchwork versions.

During her lifetime, along with publishing numerous books, Valiente was initiated into four covens in total. There was a pattern to her dances with covens—that of becoming involved, doubting provenance and patriarchal coven leadership, doing research to confirm any suspicions, then moving on. Her political alliances followed a similar structure, including a brief foray into right-wing politics during the early 1970s. Heselton suggests that during her 18-month stint with the National Front she might have in fact been undercover, spying for the state. She herself claimed disillusionment as the reason for her separation from the Front; a firm believer in women’s rights, gay rights, and civil liberties, we might wonder why she joined such an organisation at all.

In her book The Rebirth of Witchcraft (1989), Valiente was more explicit about her feminism and distaste for so many covens, stating that “we were allowed to call ourselves High Priestesses, Witch Queens and similar fancy titles; but we were still in the position of having men running things”. Valiente valued collaboration over domination, and held out hopes for a “constructive” spirituality that emphasised the environment, civil liberties and social justice rather than petty squabbles and battles over authority. More than this, she wanted to promote a witchcraft that was open to all.

In 1971, Valiente appeared in a BBC documentary about Wicca alongside Alex Sanders, founder of Alexandrian Wicca. Despite her increasing celebrity, however, she remained incredibly down to earth. An enthusiastic football fan, Valiente enjoyed betting on horses and throughout her life worked in a surprising array of jobs—including stints in factories, for a furniture company, and in the Brighton branch of Boots pharmacy. Following the death of Casimiro, she never remarried but spent her remaining 20 years with the “love of her life”, Ron Cooke, who she initiated into the Craft, with him becoming her High Priest. And so, the pair’s life came to revolve around holidays in Glastonbury, football matches on the TV, Valiente’s writing and public engagements, and the practice and study of magic.

Valiente died in 1999, two years after Ron had passed away, and her ashes were scattered around the roots of her favourite oak tree near the South Downs in East Sussex. Two of those present picked an acorn from the tree, cast it in silver, and gifted acorn pendants to those at the Museum of Witchcraft and Magic in Boscastle, Cornwall. This museum, founded by Cecil Williamson, was the successor to Williamson’s earlier iteration on the Isle of Man which Valiente had read about in 1952, and which had played such a vital role in her early life as a Wiccan. A perfectly full circle narrative for an avidly full circle witch.

The Water Issue Playlist

Listen to the Re-Enchantment Issue playlist on Spotify.

An Encounter in the Forest

Illustration © Kaitlynn Copithorne

Walking through the countryside, the cuffs of my trousers wet with dew, I had the feeling that something momentous was about to happen. It was a Saturday afternoon. My husband and I were several hours outside of London. We had taken a public footpath through the woods, not knowing where it would lead. And I can’t say what it was about that day. There was something about the way silence pervaded that hillside, the cool autumnal air, the way the leaves were on the edge of turning. Far off, where neighbouring fields met the woods, we could make out small red deer, grazing.

Eventually, we emerged from this quiet wilderness onto a busy country road. A sinking feeling; we had missed the last bus. Our feet hurt and we were tired. Dusk was on her way. There was no pavement on this narrow hedge-lined road—it would be too dangerous to walk at night. There was no other option; we would have to return the way we came.

Low on morale, we crossed the stile and began our slow descent. As we walked, the sound of traffic lessened until it was again deadly quiet. We continued like this for some time. And then we heard the sound of cracking twigs, and we turned to the ancient woodland to our left. The red deer were closer now, playing in the woods, watching us between the trees. There was a children’s den made of sticks. With some heartache, I thought of my own childhood building similar uninhabitable dwellings in such places. By day it would feel enchanting, by night like the nightmarish realm of Pan. And then more sounds. Another creature was approaching.

First came that primordial fear of facing the darkness from which we came. It took a while for me to register what I was seeing. A stag was gazing at us through the leaves, its antlers blending with the tree branches. But it was no ordinary stag. I was looking into the eyes of a White Stag.

At once, all of the childhood stories I had heard of Herne the hunter and the search for the White Stag returned to me. Without taking my eyes from it, I asked my husband if he could see it too—if it were really white. He said he could. And we spent some moments like that, eye-to-eye with this beast of myth and legend. Eventually, the White Stag turned on its hooves and cantered back into the thicket. We stayed for a while, awestruck. Should we pursue it? Two of those red deer appeared in the distance, skipping in a forest clearing. A gut feeling told me we shouldn’t.

With a new surge of energy, we continued on our way. When we had left the woods and the fields, and we were back in town, I asked my husband if we really saw it, half doubting myself again. Yes, we did, he confirmed. We had both seen it. And I felt like we were standing on the precipice of some great change.