For those experiencing lockdown without a garden or access to a green space, the past couple of months have undoubtedly been tough-going. Now available online, Camden Art Centre presents The Botanical Mind: Art, Mysticism & The Cosmic Tree, a virtual art programme which will continue to expand in the coming weeks and which offers at least a digital portal into the natural (and mystical) world.

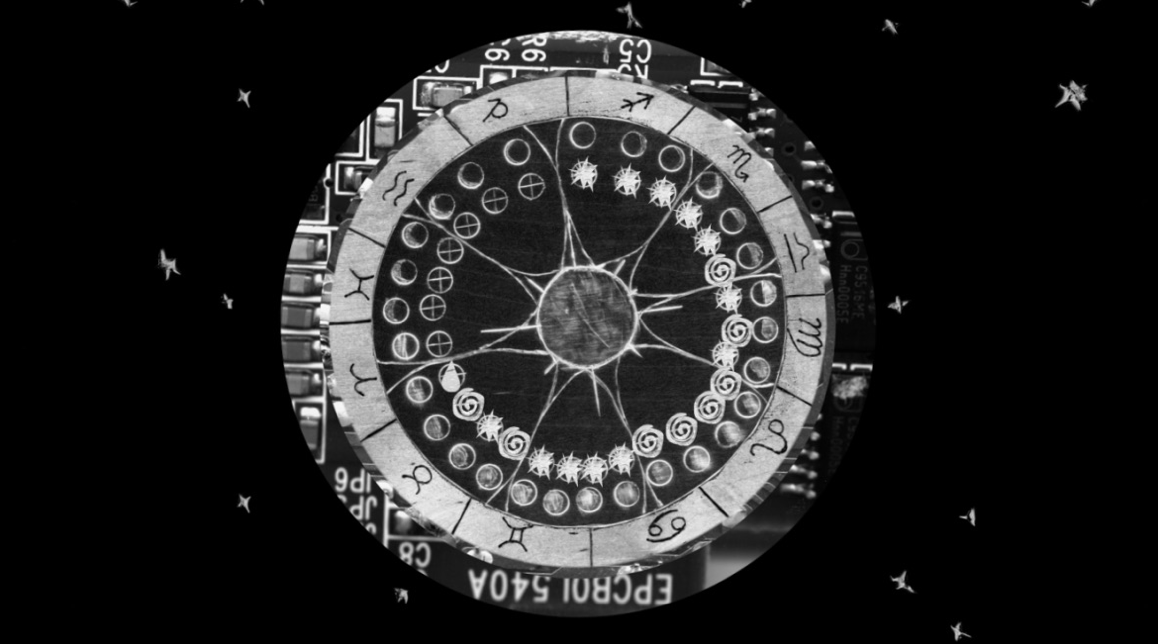

Hildegarde von Bingen, Liber Divinorum Operum (The book of divine works), 13th Century Illuminated Manuscript (detail). By concession of the Ministry for Cultural Heritage and Activities - Lucca State Library.

Among the huge variety of artworks are drawings, paintings, videos (including artist Adam Chodzko’s hypnotic ‘O, you happy roots, branch and mediatrix’ set to a composition by 12th Century mystic, Hildegard von Bingen), podcasts and thought pieces, and the series incorporates the work of global artists as well as 500 years’ worth of plant discovery.

Curated by Gina Buenfeld and Martin Clark, The Botanical Mind was conceived in a world before Covid-19 and due to open to the public on April 22nd 2020. With the pandemic forcing galleries to shut worldwide, Camden Art Centre made the decision to provide a virtual catalogue of the thoughts and ideas behind the exhibition, with a view to reopening their doors later in the year. In this way, The Botanical Mind has done what all successful living things do and adapted to its environment. Not only that, it feels like a study of our collective slowing down, with its focus on the quiet—but magical—life of plants. The series has been split into six chapters, called The Cosmic Tree, Sacred Geometry, Indigenous Cosmologies, Astrological Botany, As Within, So Without and Vegetal Ontology, and includes microscopic photography by Joachim Koester and complex molecular-inspired artwork by John Dupré and Gemma Anderson. In a single review, it would be impossible to do all the artwork justice, and so I’ve decided to focus on The Cosmic Tree (trees have always had my heart!) and what this symbol invokes.

The tree at the beginning of the world, or the centre of it, spans many cultures and religions; in The Cosmic Tree, it is explained in terms of the Axis Mundi (World Axis). At present, viewers too are rooted (I’m so sorry), and yet thanks to the internet we are able to connect to a world of creativity that shows us just how much we have in common. With wall panels from the Neo-Assyrian Empire and illustrations from Norse mythology, this chapter celebrates the tree as an omnipresent cultural image. It might bring to mind knowledge, snakes, life, fruit, language, family or all of these things, and in The Cosmic Tree, we see how they are captured in art.

Adam Chodzko, O, you happy roots, branch and mediatrix, still, screen 1, 2020. Two screen video, Hildegard von Bingen’s lingua ignotae and image recognition algorithm. Image courtesy the artist.

In Carl Jung’s work, the Liber Novus, tree illustrations abound, from The Tree of Life to The Philosophical Tree, both featured on the website. They are vivid, almost mosaic-like, from their roots to their light-filled branches. The illuminations might suggest a gateway between the natural and supernatural spheres, not unlike the shamanic beliefs found in parts of Central and South America. The watercolours of contemporary artist, Delfina Muñoz de Toro, depict lush flora and fauna set against black, and in Vimi Yuvi (Fruit of the Serpent) (2019), a blue snake coils around a flower, reaching up as if to meet the ecliptic sky. To the shaman, the snake is a powerful symbol. To the Western eye, it is inescapably Edenic, and yet the serpent shown here is as beautiful as its fruit, turning the biblical narrative somewhat upside down. Hailing from Argentina, Muñoz de Toro is inspired by the cultural practices of the Amazon-dwelling Yawanawá people, explored further in the chapter, Indigenous Cosmologies. The Yawanawá’s sacred designs, or kené, include textile-work as well as using the human body as a canvas. Footage of the Yawanawá people is available to view, as are Muñoz de Toro’s musical compositions which encompass birdsong and chanting. Whether it’s the remote reaches of the jungle, or the forests of European folklore, the tree once again inspires in us humans both the artistic and the spiritual. It seems to be with a kind of gentle dominance that trees appear in our lives, like the repeated patterns in plants (also explored here) or the meditative infinity of the mandala (also explored here!).

Vimi Yuvi, Fruit of the Serpent, 2019.

The thoughtful and collaborative nature of The Botanical Mind means there is plenty to delve into, and with forthcoming works from Gemma Anderson, Tamara Henderson, Adam Chodzko and Ghislaine Leung, the project promises to keep growing (again, please forgive me) with a calming lifeforce all of its own. Until that lovely time when we can once again see friends, family and art close up, such online projects feel like a good way to transcend the lockdown.

Annie Besant and C. W. Leadbeater, Seeing of Music, The Music of Gounod from Thought Forms, 1905. Public Domain.

The Botanical Mind: Art, Mysticism & The Cosmic Tree; Camden Art Centre online 6th May – July 31st 2020 Curated by Gina Buenfeld and Martin Clark. The Botanical Mind Podcast Series, developed and produced with Matt Williams and Alannah Chance