Molly Aitken was born in Scotland in 1991 but raised in Ireland. One of her short stories was included in the Irish Imbas 2017 Short Story Collection and she was shortlisted for Writing Magazine’s fairy tale retelling prize 2016. Her magical debut novel, The Island Child, is steeped in Irish folklore and centres on motherhood, womanhood and identity. In a review for The Telegraph, Ella Cory-Wright described Aitken’s prose as ‘exquisite’ and said ‘Aitken is an exciting new voice in Irish literature.’

Image © Christy Ku

Elizabeth Kim What inspired you to write The Island Child?

Molly Aitken For me fiction inspires fiction. Many years ago I read two fictions in the same week that synchronously came together as the idea for The Island Child. One was a scene in The Odyssey where Odysseus is shipwrecked in a storm and washes up on a tiny island where he’s found by a princess. The scene was so vivid to me I even dreamt about it. A few days later I read Riders To The Sea by the Irish playwright John Millington Synge about a family of women on one of the Aran Islands waiting to hear news of whether the last surviving son and brother had drowned. The two began to meld and I wondered how that story of a stranger washing up on an island would work if the island was Irish and the setting was a little more contemporary. However, I didn’t put pen to paper for years. Something about the story didn’t feel right for me to write...until I realised it wasn’t about the strange man but the woman who lived on the island and wanted to escape it. And that’s how Oona was born.

EK Why did you decide to set this on an imaginary island off the coast of Ireland, not somewhere we can find on a map?

MA The island, Inis, in The Island Child is based on many islands around Ireland that I was familiar with from childhood, especially Cape Clear and the Aran Islands. As a child and teenager holidaying on the islands, I felt like anything was possible there. My belief in the fairies was heightened perhaps because islands are so isolated, you are so close to nature, so at its mercy. I wanted Inis to have that magical aura that childhood brings, an essence of the otherworldly, so it felt important that it wasn’t a real place. The island throughout the story is rooted in memory, and Oona, the narrator, bends the place to fit her memories and emotions. It is in many ways a place outside of time for Oona so it felt important that although it’s based on real islands and the way those islanders lived, Inis is its own place. That also allowed me to make up my own myths and stories about it.

EK In your novel, we see fairy folklore and pre-Christian ideas blended with Christianity. What research did you do?

MA There was no specific research I did initially into the peculiar Irish phenomenon of blending Christianity with folk belief. Although I think in many Catholic cultures the dregs of pre-Christian ideas still live alongside present practices. Italy springs to mind. I grew up in this environment so I never really thought to question it. My parents weren’t religious, but I went to Christian schools (it’s hard to avoid them in Ireland) and also heard the stories of the little folk from adults all around me. For a long time I believed they were all related. The gods in Greek myths populated heaven alongside the Catholic God while the land was inhabited by the little people. There’s a wonderful belief held by some people in Ireland which I included in The Island Child that the fairies are actually fallen angels, not quite bad enough for Hell but who still cause a deal of mischief on earth. I love this explanation because it perfectly marries Christianity to folklore and that’s the power of stories. When early readers of The Island Child mentioned how odd this blend of folk Christianity was I began to research it. Most of what we know about it has been passed down orally and only in the last fifty years or so have the stories been collected into books.

EK And having grown up in the Republic of Ireland, in your experience, does this resemble the way Christianity is practised in rural Ireland today?

MA Growing up in Ireland I heard stories about the fairies from people who went to church every Sunday. As a child I visited a holy well dedicated to St Bridget where there was a tree covered in flapping rags and odd trinkets. In pre-Christian times, these wells were for a goddess or nature spirit. People are perfectly aware of this flips. The more rural in Ireland you get, the more stories and personal sightings of the little folk or even the odd banshee. At pubs in rural Ireland I heard many a ghost story and personal folk tale. I believe that being so close to nature encourages these sightings. I never heard anything about the little people in Dublin.

EK Your story veers away from the more romantic notions of little folk and revisits the terror associated with encountering them in classic fairytales. You don’t shy away from describing the more hostile aspects of living so close to nature — the things that terrified people in ancient times — the scene where the whale is cut up comes to mind. Can a magical world view and re-enchantment ever come without the terror of coming face-to-face with Pan in the wilderness?

MA Although not set in ancient times, The Island Child is about people who live in communion and friction with nature. They rely on it completely to survive but it is highly volatile and dangerous. The sea takes lives and so does the rocky land. When people live so closely to nature, it does become more threatening. In this way, the fairies who are tied to the islanders’ understanding of nature also have to be threatening. The first time Oona leaves her house on her own, she’s conflicted with joy at her freedom but also fear about what lurks in the fields and water surrounding her. As a child she has been filled up with these stories of the dangers of the land and sea in order to protect her, but this means the world beyond her mother’s cottage seems dangerous. There are fairies lurking everywhere ready to steal her away. The scene of the whale is a good example. The people of the island have a story about how they live on the back of a whale. She is their mother and protects them. When the whale washes up, it quite literally sustains them, but it’s horrific to Oona and some of the other characters. They struggle to combine the beauty of the myth with their harsh reality.

EK Myths often centre on men—did you, in your research, find stories centred on female experience?

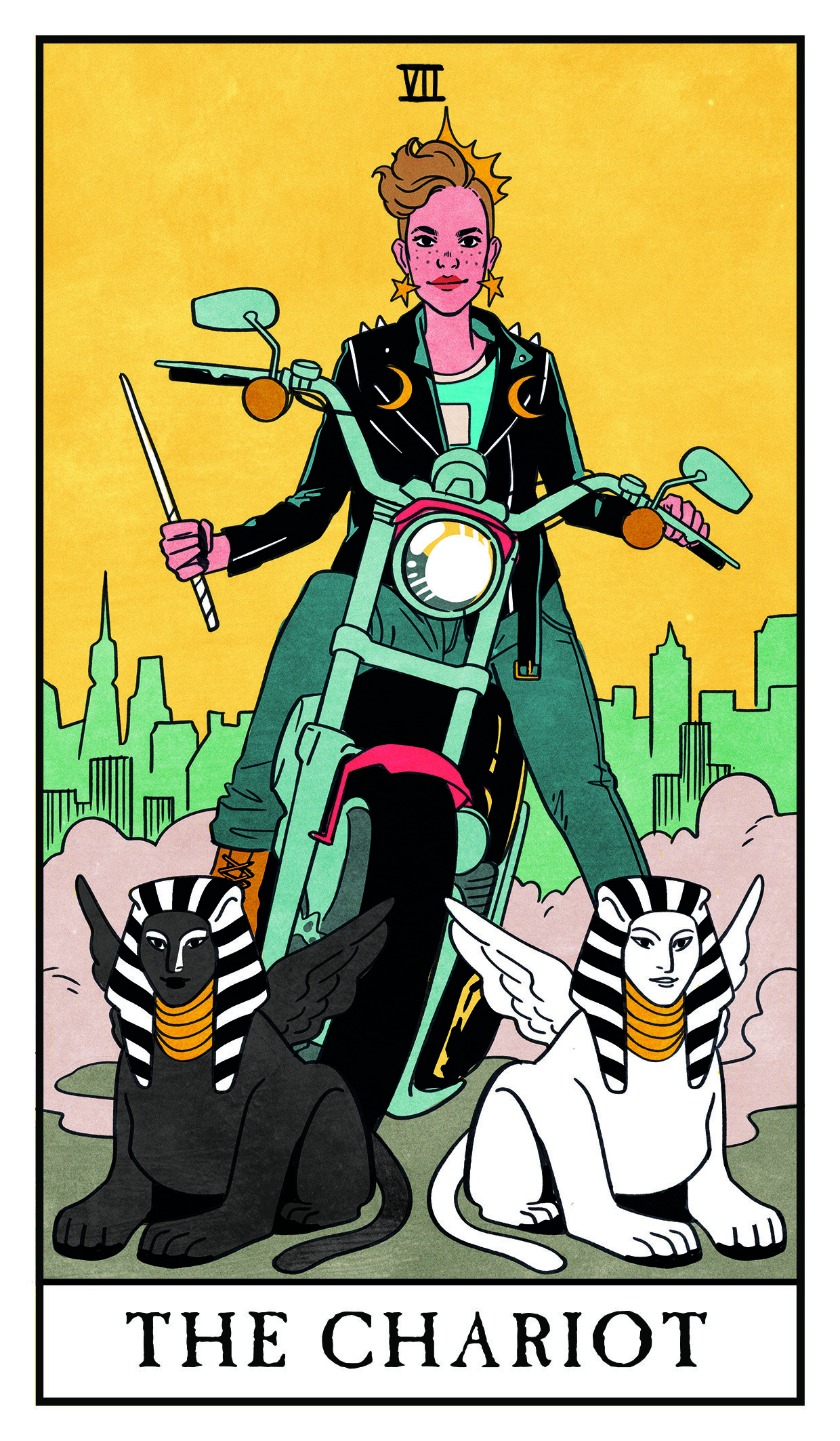

MA I’ve always been much more interested in myths about women, and women’s experience, than the swords and clatter of male narratives because they feel more familiar to me. I can relate. When that scene in The Odyssey of the hero washing up on an island came to me as a good novel idea, one of the reasons I didn’t want to write it was because the story was too familiar and therefore boring. When I realised I could tell it from the woman’s perspective and in that way reclaim it, the narrative and voice came alive. I think now is a really important time for myths about women. For so long, the ancient western stories that are remembered and honoured are about men but finally the tide is shifting and people, including myself, are becoming much more interested in re-enlivening the voices that have been silenced for so long. Amazing examples are Madeline Miller’s Circe and Natalie Haynes A Thousand Ships not to mention contemporary retellings Kamilla Shamsie’s Homefire.

The novel I’m currently writing, The Butterfly Factory is a loose retelling of the myth of Psyche. This is a very unknown story from antiquity where the woman is very powerful. It’s almost a feminine story of Hercules. When I mention this myth people are either unfamiliar with it or only know Psyche from art where she is hyper sexualised. I hope to change this a little with my writing.

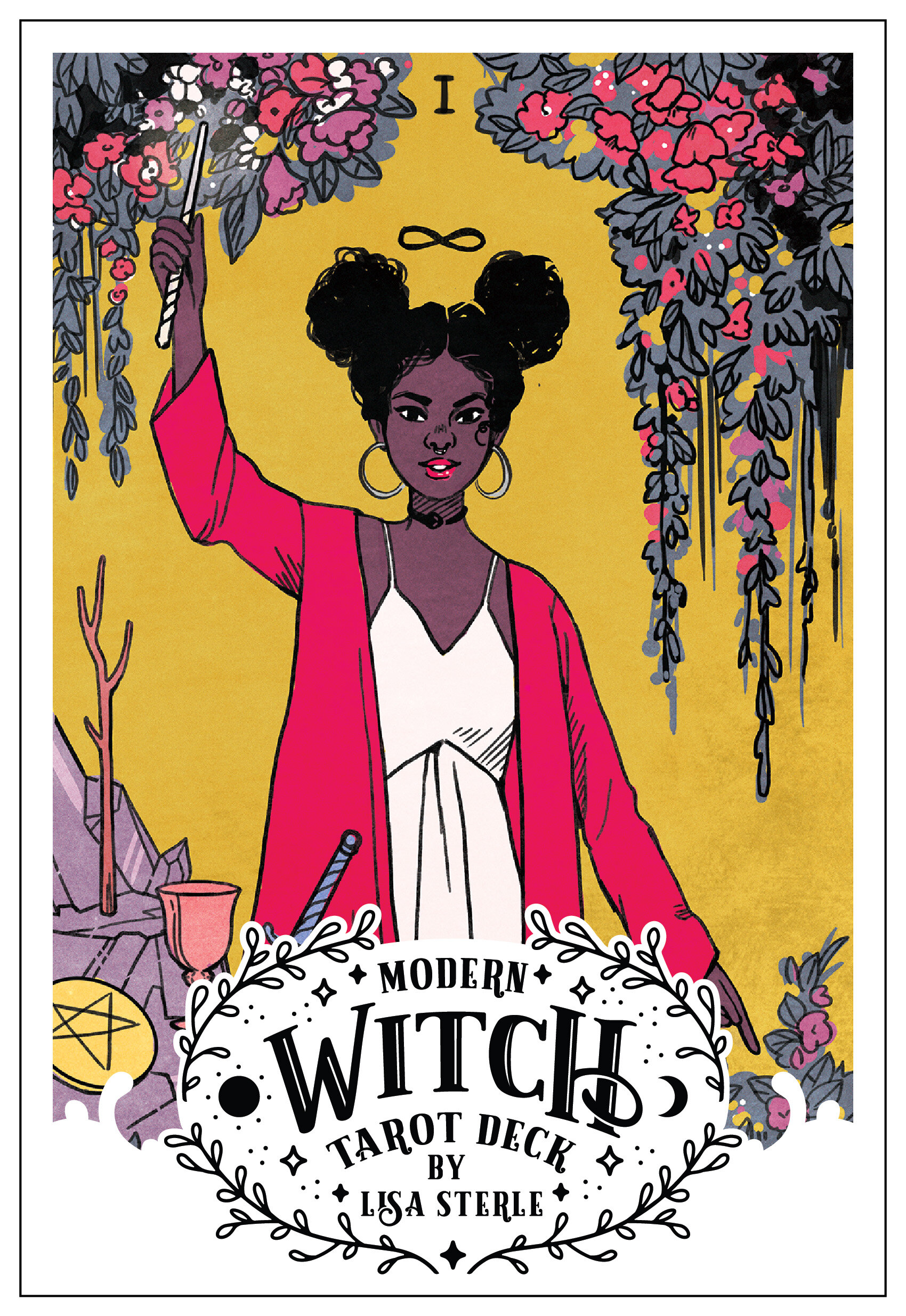

EK Do you think of Oona as a character channelling the witch archetype? Which witchy Irish figures inspired her?

MA This is such an interesting question. At the beginning of The Island Child when Oona is still young she becomes fascinated by a wild, outsider woman named Aislinn. She’s an unmarried woman who lives alone with her child and grows herbs and strange plants in her garden. She also offers healing to people who ask for it. These aspects of her make the islanders suspicious of her. She is the character who people suspect of being a witch in The Island Child, but that’s not how she sees herself. She sees herself as an independent woman who is self-sufficient and content without a husband. This is what Oona wants for her own life too. The freedom of what this small community views as a witch.

EK Oona is haunted by the island that shaped her; the lines between her and that setting blur. Can we ever escape where we came from?

MA This is a complicated question without one simple answer. In The Island Child Oona is haunted by her past because she refuses to acknowledge it. Once she left the island Inis for Canada, she never speaks about where she comes from or who she is because of her home. Her past is particularly traumatic. The main message of The Island Child and what I hope readers will take away from it is that stories and telling our stories can be healing. Only once Oona begins to acknowledge her past does she then transform it into something she can examine without fear. I don’t think she will ever escape it but she can become less fearful. She can face it. Speaking the words and telling the story of her past through the novel almost breaks the spell she has allowed her past to cast over her. Words shine light into the dark corners and shows her she can live with them. That’s the power of story.

EK Finally, which other books about the sea and/or Irish mythology would you recommend to readers?

MA While writing The Island Child I read many books including ‘Women and the Sea: A Reading List’ as well as The Country Girls trilogy by Edna O’Brien, The Good People by Hannah Kent and the particularly magical and strange Himself by Jess Kidd. I also recommend the stories of Peig Sayers who was one of the greatest storytellers Ireland has ever had.